Phil Ball and Juanjo Moran explain the Spanish model of the feeder club system

Phil Ball and Juanjo Moran explain the Spanish model of the feeder club system

The Spanish league system is something of an oddity in Europe. There are basically three divisions worthy of note – The First, the Second A‚ and the Second B‚ after which there lies a morass of regional feeder leagues containing a hotch-potch of small town clubs, some forgotten bigger clubs, clubs who represent barrios (neighbourhoods), of larger cities that were once independent of the current conurbation, and some reserve sides.

Most of the top clubs have their reserve sides, referred to as the cantera (quarry), in either A or B. The teams are called, unsurprisingly, Real Madrid B and so on. The players can only play for these teams so long as they do not belong to the official first team squad announced at the beginning of the season. Similarly, there is no downward movement either, since a member of the first-team squad, whether he is playing regularly or not, cannot turn out for the reserves, as in England.

The consequences of this are fairly easy to see, the most serious one being that in teams such as Barcelona and Real Madrid – who buy up all the half-decent players from everywhere else just in case – footballers watch their lives rot away sitting on the bench, if they’re lucky, or more likely from the stands on match days.

Barcelona have Victor Baía between the posts whilst Lopetegui, a full international, may get a game every blue moon and Busquets, an ever-present under Cruyff, has to make do with training sessions for his match practice. Barcelona B, currently floundering below the mid-table point of 2nd A‚ could well do with some of the quality that lounges above – not to mention other sides in the 1st Division for whom most of the inactive players from Barcelona’s main squad would represent a luxury. The loan system exits here, but is much more formalized. Players are loaned out for whole seasons with a stipulation in the agreement that they come home should they start playing at all decently.

The reserve sides in 2nd A cannot be promoted whilst their better halves are in the top division. Their existence is consequently a rather odd one, divorced from the day-to-day relationship with the first team which would no doubt be of benefit to them and forced into a sort of phoney bon ami where they must generate their own enthusiasm, each player presumably hoping that he will make the jump next year. And of course, many do not, playing out much of their careers in limbo-land.

Valladolid, Zaragoza and Logroñes among others all have their quarry sides in 2nd B‚ which also guarantees negative consequences. The players, bumbling away in a league of dubious quality, find the leap to Division One something of an unbridgeable abyss.

No wonder the Spanish League has welcomed the post-Bosman party with open arms. Such is the quantity of non-Spanish flesh currently playing in all divisions that the National Union of Players is threatening action unless a ceiling is put on the importation. It was always bound to be an issue, but it is not surprising that it is in Spain where the issue is rearing its head most seriously.

Reserve sides were not always saddled with such unimaginative nomenclature. Before legislation was passed here in 1990, Real Madrid B were called Castilla. Wonderfully, despite 2nd Div status they got to the Cup Final in 1980, against… Real Madrid. The game was played in the Bernabeu, and the 1st team (with Laurie Cunningham) won 6-1.

This year, something positive has also happened. Eibar, a tiny club from a an industrial speck of a town in the North whose equidistance between Real Sociedad and Athletic Bilbao had traditionally seen it playing the role of nursery club, has suddenly found itself bursting at the seams with a squad of young players released from the above-mentioned, over-subscribed clubs. Instead of wasting their lives away in reserve squads, these young bucks have taken to a real challenge with relish, with potentially bizarre consequences.

Eibar currently lie second in Division 2 A‚ and are seriously threatening promotion. With average crowds of 1,500 and a ground capacity of 4,500, success at the end of the season would represent the mother of all fairytales – and as you can imagine, the TV money men from Division 1 are sweating all the way to their committee meetings. How nice if the nursery-team syndrome were turned on its head and the clubs they were supposed to be feeding‚ have to pay them a timorous visit next season. Someone will put a spanner in the works – it’s inevitable. But meanwhile, Eibar dream on.

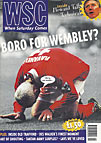

From WSC 122 April 1997. What was happening this month