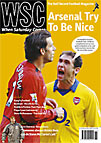

Peter Robinson has photographed football across five decades, as his new book records. But in spite of his unparalleled career, the Premier League want him to start again

Peter Robinson has photographed football across five decades, as his new book records. But in spite of his unparalleled career, the Premier League want him to start again

My first involvement with football came through meeting someone I knew in the street who told me that the Football League Review was looking for a regular photographer. This was the League’s official magazine, produced on a shoestring initially. It was included as an optional insert with club programmes. Most of the lower division clubs took it because they needed something to pad out their programmes, most of which were only the size of the Review itself. Some of the wealthier clubs with bigger programmes didn’t want it, though, and that affected their level of co-operation with me when it came to taking pictures. The League wanted a range of clubs to feature, though you couldn’t hope to cover all 92 in a season even when the Review went weekly.

I’d take a lot of posed pictures of players in unusual locations, with street signs and so on. This was before players had agents so I could contact them by going to clubs. The players were quite happy to jump in a car and go – I think it helped that I wasn’t a football nut so I wouldn’t be asking them about this match or that manager. I did a lot of pictures with George Best at his ultra-modern house in Cheshire, in nightclubs and at his boutique. But that was among the material that got thrown away by the janitor at the League offices when they had a clear-out of the basement one day.

I was conscious that I was different when I talked with other photographers at games. Their references were totally different to mine and they were looking for different things. I felt that you didn’t just have to start photographing when the ref blew his whistle. I was interested in the whole build-up to the game, even during the week before. Football in the 1960s in some ways hadn’t changed much since the Thirties. The people looked different but the environment was the same – the grounds themselves, the turnstiles and the terraces, and the fact that a lot of people still got there on public transport rather than in cars.

Clubs and the Football Association didn’t employ their own photographers then, so being the only one connected with a football organisation on a permanent basis helped me get a job with FIFA, beginning with the 1970 World Cup, through to 1994. It turned out, though, that most of the work was photographing meetings. At the 1974 World Cup, I missed the West Germany v East Germany game because I had to take a team picture of the Yugoslavia team for FIFA’s official report. I missed other games because I had to update the referees’ handbook; I spent days photographing people blowing whistles when I should have been at matches. That changed once FIFA starting working with the marketing group ISL, after which they needed shots of all the sponsors’ perimeter advertising at every match, so I had to hire people to help me out.

Even though I have been photographing football for 40 years, I can’t get into Premier League games today because I haven’t got the required licence, which was introduced in the late 1990s. To get one, I was told that I would have to photograph amateur football on parks and recreation grounds and be published in local newspapers. After a year of doing that, I would probably get a licence to photograph Football League games, then after a year of that, they would consider giving me access for the Premier League. Even then, my licence wouldn’t be renewed at the end of a season because you need to have at least 50 pictures in magazines and papers that come out within a short space of time after the game. These can’t be images that are put in a book – they want images digitally transmitted and published almost straight away.

I picked up three books about football recently. The quality of printing and photography is mind-bogglingly good. I couldn’t fault a single photo on a technical aspect, but you’d be falling asleep after a few pages because every picture is pretty similar. If you took one picture out of such a book you could say it was great, but seen all together there’s a uniformity now.

The way the football authorities see the game now is the way they want it reflected back to them – fans in replica shirts with painted faces. Euro 96 confirmed that this is the way football will be sold. My view is simply that I don’t want to go into a game with any restrictions.

From WSC 201 November 2003. What was happening this month