Duncan Young recalls how Mick Ferguson did his job, thereby relegating himself, and questions new rules that could make the dilema Ferguson faced a common one

Duncan Young recalls how Mick Ferguson did his job, thereby relegating himself, and questions new rules that could make the dilema Ferguson faced a common one

Imagine it’s the last game of the season. You’re a striker. You’ve only got the keeper to beat to score the goal that keeps your team in the top division. There’s just one problem. You’re on loan from another club and if you score they’re the ones going down. What would you do?

Mick Ferguson knows. He was on loan from Birmingham City to Coventry in 1984 and scored in the 2-1 win over Norwich that saved Coventry and condemned Birmingham to the drop. “I relegated myself into the Second Division.”

Mick was still recovering from a hernia operation but answered the call of the club at which he had previously spent 11 happy years. He contributed four goals in seven games during Coventry’s run-in, but then had to go back to Birmingham and face life in a lower division for the first time. “I do regret sending Birmingham into the Second Division, but when I pull a shirt on I pull it on to win the game.”

This kind of dilemma concerns Mick McGuire, once a team-mate of Ferguson and now the deputy chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association. He cites the example of Danny Mills playing recently for Middlesbrough against Leeds, who own his registration, and ponders the reaction if Mills scored a wonder-goal late in the season that severely influences both clubs’ fortunes.

He’s also worried that relaxing the rules to allow loans between Premiership sides threatens a significant dilution of the competition’s appeal. Clubs are now permitted two domestic loan players at a time and four over a season, allowing up to 80 such moves between now and next May. “Our view is that certainly spectators would see that as almost their own clubs losing their identity… I think it devalues the Premier League, which is supposed to be the most important league in the world.”

The loan system is being thrown into sharp focus because of the sudden financial crisis within the English game, the scrutiny magnified by transfer windows grouping deals together. Loans were originally intended as a very short-term fix for financial or injury crises. They have been expanded in recent years to allow a full season of lower division experience for talented youngsters, but the system is now being targeted at the highest level as a strategy to rival or replace full transfers.

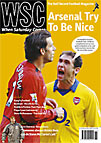

Currently, 28 players are on loan at Premiership sides, 13 of whom belong to other Premiership clubs. Arsenal are providing three of those and others elsewhere to decrease their wage bill. Conversely, Leeds are trying to acquire players cheaply and quickly by initiating six of the 12 loans from foreign clubs, an area currently without restrictions. If Leeds survive on this strategy it is sure to provoke urgent debate. More controversially still, Portsmouth have acquired Alexei Smertin from Chelsea for the season within days of his arrival at Stamford Bridge, highlighting another facet of the new rules that makes many uneasy. Beleaguered Premiership chairmen were keen to make changes, but McGuire says: “Our concern is that it hasn’t been thought through thoroughly.”

Professor Tom Cannon, non-executive chairman at Checksure, an organisation that provides credit ratings on companies, and an expert on football finance, feels that by the end of this season it is inevitable that many of these issues will have come to a head and forced a serious examination of the regulation of player ownership and transfers. As well as issues within the football community, Cannon foresees problems with increasing use of loans in the eyes of those investing in the game. “If you’re a club that’s listed on the stock market, you’re obliged to put the value of your players on your balance sheet. If you take them off the balance sheet and lend them to another club, it makes it very difficult to assess the finances of the club.” He believes accounting issues also prevent the English game from adopting the Italian concept of co-ownership, where clubs effectively loan out a player by selling half of his contract, bringing in immediate transfer money while increasing the incentive of the club taking the player to treat him well.

Cannon voices fears that liberal use of loans, though attractive in the short term, prevents clubs from developing playing talent that would help ensure their long-term survival. Many fans share this concern, reluctant to make an emotional and financial investment in players with little overt affiliation to their clubs. Even established stars have increasingly demonstrated that professional loyalty is inevitably swayed by finance and politics.

Many youngsters received unexpected opportunities courtesy of the maligned transfer windows. Clubs should think carefully before sidelining these popular products of expensive youth schemes – all their futures might depend on it.

From WSC 201 November 2003. What was happening this month