An English football club is now the must-have accessory for discriminating billionaires from all around the world – but does this trend make any financial sense? David Wangerin wonders if there is enough cash – and enough optimistic fans to part with it – to sustain the current booming revenues

An English football club is now the must-have accessory for discriminating billionaires from all around the world – but does this trend make any financial sense? David Wangerin wonders if there is enough cash – and enough optimistic fans to part with it – to sustain the current booming revenues

“As a global brand,” the Independent claimed recently, “the Premiership is becoming sport’s equivalent of Coca-Cola and McDonald’s.” Can this be true? Certainly the success of fizzy-drink manufacturers and fast-food restaurants is not measured by trophies. But as the level of financial interest spreads across the globe, the league’s international reach seems to be rapidly approaching that of the junk-food leviathans. Curiously, much of this interest has not originated in traditional footballing strongholds, but in the game’s equivalent of the emerging markets – and America in particular.

For all the media fascination, it remains a little unclear why English football is such a tempting proposition for foreign, and in particular American, billionaires who, it seems, don’t know a cup tie from a flat back four. Even the Financial Times, which recently devoted an entire page to Why English football clubs are being snapped up by foreign investors, seemed rather bereft of answers. The “marketing opportunities that previous owners have been unwilling or unable to exploit” was its educated guess; apparently, the Glazers of Manchester United “see ways to improve the international marketing and branding of the club”. It’s a refrain that has been sung with considerable regularity over the summer: how Paul Allen, the Microsoft billionaire reportedly eyeing up Southampton, has marketed and branded his Seattle Seahawks to within an inch of their gridiron life; how even the least successful of Stan Kroenke’s Colorado entities possesses more commercial acumen than Arsenal.

Not even the FT, though, is prepared to attach a pound sign to all this untapped marketing opportunity. The basis of the assumption seems to be that British supporters are just as keen as American ones to part with their money in the name of club loyalty. Maybe that’s the case; certainly you won’t see fans in the United States queuing for hours to be the among the first to purchase their team’s latest strip. When foreign investors speak of being impressed with the “passion” of the English supporter, perhaps this is what they mean.

Alongside the sponsored polyester there’s all that TV money – not just from Sky and Setanta, but from further afield (this year a new company is bringing a pay-TV package to Africa: eight Premier League games a weekend). Here, too, there appears to be an underlying assumption: that the £25 million to £50m a year each top-flight club now receives from broadcasting rights is merely the start of an upward spiral, that the appeal of English football will continue to spread to new audiences, markets, communities or whatever it is these things now spread to.

But it’s the stateside interest in the mega-clubs in particular that catches the eye, and the attraction is all the more understandable when one considers how the most successful of America’s professional leagues operates. Nearly half a century ago, the owners of NFL franchises opted to pool their TV income and split it equally; it was, they agreed, in everyone’s interest for no team to become much bigger or smaller than the others. The collective ethos also applies to virtually all the league’s merchandising rights: everything from $1,000 leather recliners to $15 DVDs. Parity, in fact, has been almost as important a factor as TV money in the NFL’s rise to national supremacy. Of course, in the United States there is no equivalent of the G-14 – and the days of Wigan Athletic sharing in the proceeds from MUTV, or Fulham benefiting from an uptake in replica Arsenal shirts, seem very far off indeed.

How paradoxical, then, that while the English boast of their fair-mindedness and even-handedness in sport, the rampant self-interest of their football clubs should be so manifest – and evidently such a turn-on for the US investor: the bigger you are, the bigger you’ll become. It’s hardly surprising that Americans have snapped up at least a piece of most of the usual Champions League suspects: Liverpool, Arsenal and Manchester United. For them, the European component is a thick layer of financial icing; over there, teams compete for one trophy at a time, and rarely beyond their own borders.

But the Premier League, in all its unbalanced glory, represents the cake, and quite a luscious one, too. While choosing the next Super Bowl victors has become something of a lottery (in the last decade, only one team has won more than one), hardly anyone envisions a surprise winner of this season’s Premier League and the Champions League places seem almost predetermined. Few things will warm the heart of a entrepreneur more than the thought of having cornered a market and, in the sporting canon, the upper reaches of the Premier League are as about as close to nirvana as you can get. Given the lopsided nature of foreign interest – apparently 14 per cent of all soccer fans in China claim to own a Man Utd jersey – we can expect the league’s financial strength to become even more concentrated in the years ahead.

Yet it isn’t all gravy. Playing at the highest level means assembling a formidable team and increasingly this has come to mean one that costs an awful lot of money. Eight-digit transfer fees are not a conspicuous feature of the NFL; salary caps are. You need to sell a lot of TV subscriptions to buy Fernando Torres and you can’t get him for nothing in a college draft.

But could the Premier League place a limit on wages without arousing the displeasure of the European courts – or, more to the point, without destroying much of the worldwide allure that has attracted the global audience in the first place? We all know how careful Major League Soccer has been to avoid the wage profligacy of the NASL – and how it has struggled for credibility in the eyes of many fans. Its solution, it seems, has been to throw money at David Beckham.

Without a salary cap, or something like it, the Premier League’s financial strategy seems to hinge on television revenues outpacing players’ wages – or, more precisely, reining in the owners’ enthusiasm for paying over the odds for talent. So far, they’ve succeeded; the wages/revenue ratio is lower than in most other European leagues. In the end, though, they are almost certain to fail. Wages are rising at 20 per cent a year – and North America, which has a few decades’ head start on this stuff, has frequently seen its big leagues groan under the financial strain of megalomania.

Clearly the FA could make everything a lot easier by dissuading the owners from paying such high wages through a more rigid insistence that clubs start to balance their books, or at least exercise a business-like degree of financial prudence. In the last financial year for which figures are available, 2005-06, Chelsea lost £80m – and that represented a sizable improvement on the previous figure; servicing the debt of the current champions runs to £60m a year. Does this represent success or failure?

Most fans, thank goodness, measure success the old-fashioned way, and it is their unrelenting optimism that the Premier League needs, perhaps more than ever, to survive. So long as supporters of, say, Newcastle or Tottenham imagine the perfect storm that propels their team to glory, and the novelty of a season or two in the sun draws in fans of the yo-yo teams, the figures will continue to add up. Yet as the playing field becomes ever more tilted, how much longer before the domination of the moneyed few begins to wear thin? More-over, what about those who pay the players’ wages – not just the folk passing through turnstiles, but the millions of armchair viewers from Basingstoke to Bangkok who might tire of the predictability?

By then the Yanks may have sold up and gone home. Though the Glazers maintain they have not come to Manchester merely to asset-flip their highly leveraged quarry, they could hardly say otherwise, and they will know that Alan Sugar has trousered something like £38m from his holding in Spurs, an enterprise he characteristically dismissed as a “complete waste of my time”.

For an uneasy glimpse into the future, consider Scotland, where the Old Firm have become so bored by their domestic monopoly that they now gaze longingly towards Soho Square while the rest of the SPL struggles to produce a five-figure gate. The problem confronting Rangers and Celtic is not that the other Scottish clubs lack their ambition; it’s that the mighty twosome have not been willing to share their financial success. Without losers, there can be no winners.

Some seem to disagree – including, most recently, The Economist, free-market sceptre ever to the fore. Grumbling that “there is more to sport than watching too well matched teams vie for supremacy”, it maintains that “measures to increase equality within a league take the edge off competition and therefore, presumably, off the terror that drives sportsmen to excellence”. To many, this logic will be impenetrable; isn’t the uncertainty of outcome the raison d’être of sport? Likewise, the article’s claim that basketball’s NBA has “lost some of its shine” since Michael Jordan led the Chicago Bulls to umpteen championships misses the wider picture. It’s possible for the Bulls (or any rival franchise, for that matter) to fashion a similarly imposing dynasty at some point – and to do so will not necessitate some uniquely gargantuan level of investment. Can the same be said of football?

Admittedly, not every Yank is coming in at the top. Randy Lerner has stumped up for Aston Villa, the Premier League’s middling club nonpareil, but the Independent claims he “genuinely admires the history and tradition of Villa, and will be content to break even”. Allen, meanwhile, is said to have his eyes on Southampton because it’s one of the few places he can moor his colossal yacht. (What has attracted another group to a second‑tier club £28m in debt remains to be seen; obviously Manhattan Capital Sports Partners see Coventry City in loftier terms than most.)

The tradition of ego-tripping owners, of course, is nearly as old as professional football itself. The difference in the 21st century may be only in the scale of the trip and the nationalities involved. Indeed, running a professional club has never represented a hard-nosed business proposition so much as a dalliance for the moneyed fan, or a status symbol within a privileged community. Flint-hearted rapacious capitalists are busy looking at property, hedge funds and things to do with China, not Bolton Wanderers. The acid test of the game’s real financial appeal is probably the utter lack of interest from private equity, which continues to gobble up a bewildering variety of companies from all walks of commerce, but draws the line at men chasing a ball.

English football as sport’s McDonald’s? The golden arches could survive the loss of the Big Mac and the Happy Meal; without the mega-clubs the Premier League falls apart. But sport doesn’t survive on brand leverage, it needs competition. As the “greatest league in the world” begins its latest assault on the world’s television screens, let’s hope that point isn’t in danger of being lost.

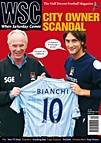

From WSC 247 September 2007