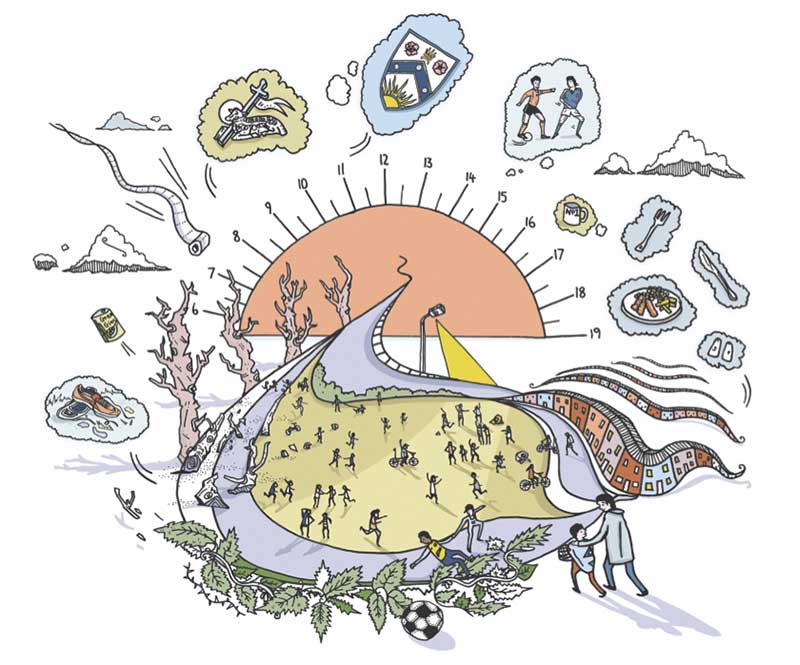

Across the country any patch of grass could be turned into a makeshift pitch, with games lasting hours – as long as the ball didn’t get lose in the nettles

12 January ~ My father and my son have both played football for money. Cameron, my son, plays centre-half for the Preston North End youth team that last year got to the last eight of the FA Youth Cup, the club’s best showing in the competition for 50 years. My father played semi-professionally for Lowestoft Town back in the 1950s. As for myself, well the talent skipped a generation and I never got that far, but I have great memories. Memories are important.

We had a scrap of green at the end of our road imaginatively called The Green, where we would play mass games of 20-or-so-a-side football. They would start more like three against two, but as kids came past they would join in as the game picked up momentum.

The game would then proceed uninterrupted, carrying on even if some kids went home for lunch and came back, often then being put on the opposite side as numbers dictated. Scores would be rigorously kept, and there never seemed to be much in it either way – 47-45 wouldn’t be an unusual scoreline. In the summer you’d go home for your tea and come out with the game still going on.

No adults intervened, except occasionally when a dad would, only half jokingly, join in for a bit, showing off his dad-skill and telling us how he could have made it if it wasn’t for his knee/the army getting in the way. The said dad would run around for a bit before hobbling off with a reoccurrence of whatever it was that was wrong in the first place, or collapse in a coughing fit mouthing the word emphysema.

The dimensions of the pitch were only notionally defined, nettles partly down one side, with dead-reckoning the only way to gauge beyond, and the road down the other with a solitary yellow street lamp providing “floodlights” for evening play. Of course jumpers were used as goalposts but it could also be an old cricket stump or even someone’s bike, though this was unsatisfactory as it led to arguments about which part of the bike constituted the actual post, or its owner getting fed up with his bike being whacked and riding off home, thus bringing the game to a halt until a new goalpost could be invented.

There was never a referee, contentious decisions were resolved by on-field arbitration and threats of violence, and we all learned a bit of give and take. I’m sure modern coaches would be aghast, but we learned to keep hold of the ball. If you passed it in a 20-a-side you might not see it again for 15 minutes. If you got a chance to shoot, you took it, for similar reasons. Though there was no tippy-tappy, and scant regard for positional play, the emphasis was on imitating individual skills we’d seen professional players do on the telly. Willie Carr and Ernie Hunt’s flick-the-ball-up free-kick for Coventry in 1971 was endlessly recreated, as was the debate about the validity of the goal; Ray Crawford scoring for Colchester to sensationally knock Leeds out of the FA Cup the same season; and any attempt at a volley had to be accompanied by the cry of “Porterfield” to make Sunderland’s winner in the 1973 FA Cup final, though much less with the attendant “One-Nil” from commentator David Coleman upon successful execution.

After the 1974 World Cup the games were marked by everyone attempting a Cruyff turn any time they got the ball. The problem with that skill being that, as the word “turn” might suggest, you end up facing the other way. Many Cruyff turns concluded with the player being confused that they were now facing their own goal with no option but to pass it back to the keeper. Though that was legal then.

My dad had been a decent player, and if it hadn’t been for the army and his knee, who knows. He would occasionally come down the green to tell us it was tea-time and bang a couple in, always hard, low and in the corner that no kid would want to get in the way of. He hit the ball harder than anyone I have ever seen, pro or amateur, before or since. Then he’d take us home while the remaining players tried to get the ball out from where it had got stuck in the nettles.

After a time our games became so popular with outsiders coming from other parts of town that lads from another estate formed their own side and we played them in a kind of representative match on the green. Then parents took over and formed a club from the two teams, who played on proper pitches, with lines and corner flags, in organised leagues and had committees and whatever. It all became official, with adults in charge. The club were very successful but it was never as much fun for the kids, it was mainly for the parents now.

They built houses on the green, and my dad has dementia. He would be so proud that his grandson is coming through the professional ranks at Preston, but it has no meaning for him any more. I keep him up to date and he’s been to watch but he doesn’t really know what’s going on. It hurts so much but there is nothing that can be done, except, for those of us still able, to remember. Steve Day

Illustration by Adam Doughty

This article first appeared in WSC 371, January 2018. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more details here