Football’s journey through the English media

Football’s journey through the English media

by Roger Domeneghetti

Ockley Books, £12.99

Reviewed by Tom Davies

From WSC 339 May 2015

We are frequently told that both the media and football have become distortingly all-pervasive, so a history of the relationship between the two would appear long overdue. In this exhaustively well-researched book Roger Domeneghetti delves deeply not just into the earliest histories of both but into what initially seem like diversionary tangents – betting, gaming and comic strips. If these are occasionally longer than they need to be, they do at least fit the author’s wider, convincing narrative of mutual interdependence.

Tracing this many-tentacled history, from the newspaper boom in the late 19th century through to the Premier League, Sky and Twitter, it is obvious how football and the media industry have always fed off each other. We may rail against kick-off times being switched at the behest of TV companies but the “traditional” Saturday 3pm start is rooted in media demands. Regional newspapers in the late 1800s required standardised kick-off times to suit Saturday evening edition deadlines. Into the 20th century, early newsreels looked to play up talking points and personalities. Sport drove radio sales and provided events for the newly established BBC to build itself around.

A common theme is the authorities’ inability to prevent themselves being outwitted, or to protect the game’s wider interests. From the wrangling with the BBC that obstructed the broadcast of inter-war Cup finals to the way the FA allowed themselves to be outflanked by the TV companies and Premier League, wearily familiar shortcomings persist.

The BBC’s agreement to pay the FA £1,000 to broadcast the 1953 FA Cup final “set the template for football coverage to this day”, not least in investing the “Matthews final” with symbolism. Competition between broadcasters changed the game again: “If the football authorities were unclear as to how exactly their relationship with television should develop, neither the BBC nor their rivals had any such doubts,” writes Domeneghetti.

The chapter on the development of newspaper journalism sheds light on the changing status of players and their relationship with reporters, as well as on the way those papers have altered, with the expansion of broadsheet coverage flattening their distinction with the red tops; writers move between both with increasing frequency. Fanzines are also given their due for changing how football was written about in the mainstream.

Domeneghetti is a press box regular himself and writes about football for the Morning Star, so as might be expected a strong social-political context frames his narrative. This, and a breezy conversational style, ensures that the dominant perspective here is that of the ordinary fan/reader/viewer. Media-analyst business-speak is thankfully lacking.

Of course we end on blogs and social media, which have given both fans and players more of a voice while posing challenges to the traditional industry. “The process of becoming a football writer’s become more democratised,” Jonathan Wilson points out here, yet making a living from it becomes ever more precarious. The contention that football is central to new media might be overstated, but not by much, though the deaths of various sectors (radio, newspapers) have been predicted many times, and not always accurately. Instead, they’ve muddled through, much like clubs themselves.

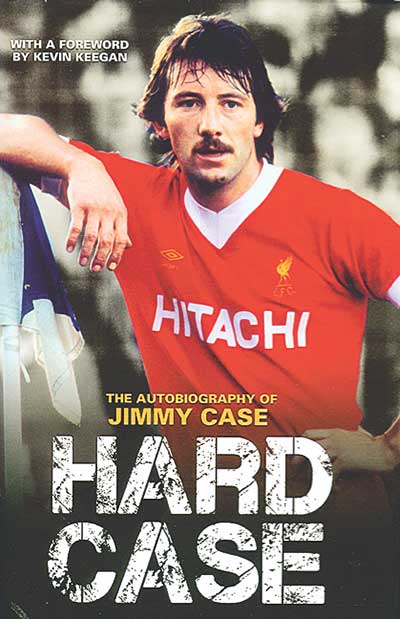

The autobiography of Jimmy Case

The autobiography of Jimmy Case In search of

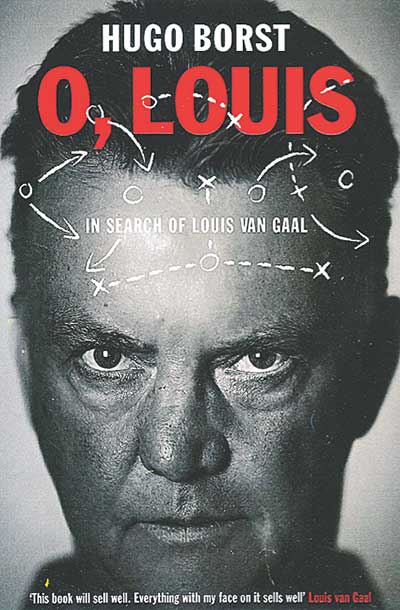

Louis van Gaal

In search of

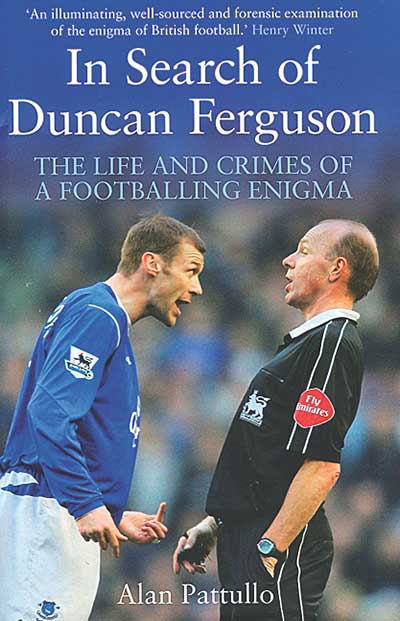

Louis van Gaal The life and crimes of

a footballing enigma

The life and crimes of

a footballing enigma The meaning and making of English football

The meaning and making of English football