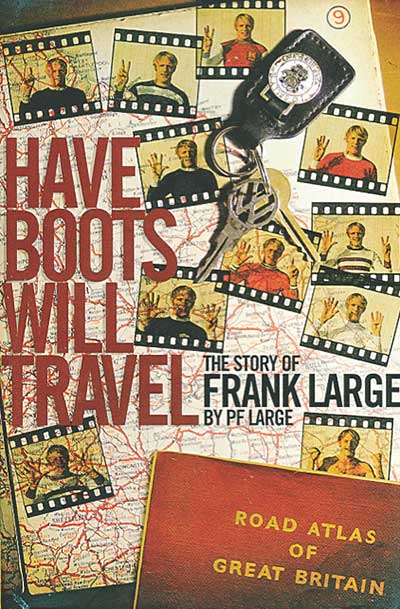

The story of Frank Large

The story of Frank Large

by P F Large

Pitch Publishing, £17.99

Reviewed by Alan Fisher

From WSC 336 February 2015

Growing up in the early 1960s, I got to know the players not through television or the papers but via my collection of bubble gum cards. On the front was a colour photo of my heroes, I devoured the brief biography on the back. Many times I shuffled the pack to create imaginary teams but one man always led the line.

Frank Large was the epitome of what I believed a centre-forward should be. Rock solid, over six foot tall, his rugged face battered, I presumed, from aerial battles with similarly uncompromising defenders. The right attributes too: “Honest, works hard, good in the air.” False nines, a pivot, mobile and pacy, I get it, times have changed but that image remains.

Large played for nine League clubs between 1958 and 1973, a total of 629 appearances including three spells at Northampton Town. His career spanned four divisions and he scored goals in all of them, well over 200 in total.

Large’s assessment of his talents is characteristically straightforward: “I can only do one thing but I’m good at it.” The story of this engaging, open man is lovingly told by his son through match reports, personal memories and interviews with ex-pros and managers, including his boss at Fulham Bobby Robson, who speaks with the humour and tenderness that footballers of a certain generation reserve for team-mates who they respect as a professional and friend. There’s a theme though – knock it up to Frank, Frank gets on the end of it, Frank never gives up.

Managers wanted him, often to give that extra push for promotion or to stave off relegation. Yet he was also easily dispensable as these same managers looked to upgrade. In 1966 alone he played for Carlisle, Oldham and Northampton. If he had regrets, he seldom showed them because this proud man was grateful for the chance to play.

There’s no in-depth analysis but the many anecdotes portray the life of this football man as a world away from that of today’s top professionals. Arriving at Halifax, his first club, he looked so bedraggled the other players gave him clothes. His reward for a cup run with Northampton was four new tyres for his second-hand turquoise Mini Clubman. There are many more and enjoyable they are too.

Perhaps the most telling insight comes when the game has finished with him. Returning home after his first morning in a factory, lungs and eyes chocked with toxic dust, he vows never to return yet picks himself up and endures the Dickensian conditions, 60 hours a week for 11 years, to provide for his family.

Frank Large died in 2003 aged 63, content in retirement in Ireland. His son’s readable, pleasing account does ample justice both to his father and a bygone age of football. Then again, Large will always be fondly remembered by supporters across the country as much for his wholehearted approach as for his goals. One of his most important for Leicester in Division One is described thus: “Frank slides in on his arse and crashes a shot into the top corner.” That’s my kind of centre-forward.

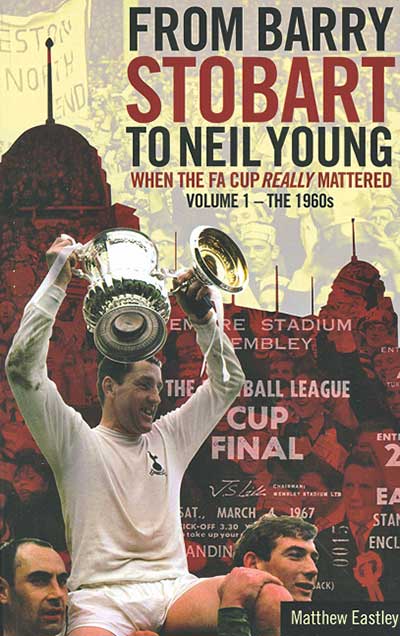

From Barry Stobart

To Neil Young

From Barry Stobart

To Neil Young The man who said no to England

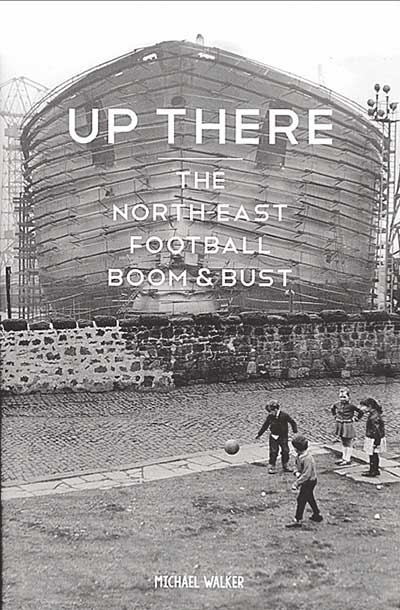

The man who said no to England The north-east, football, boom & bust

The north-east, football, boom & bust The story of

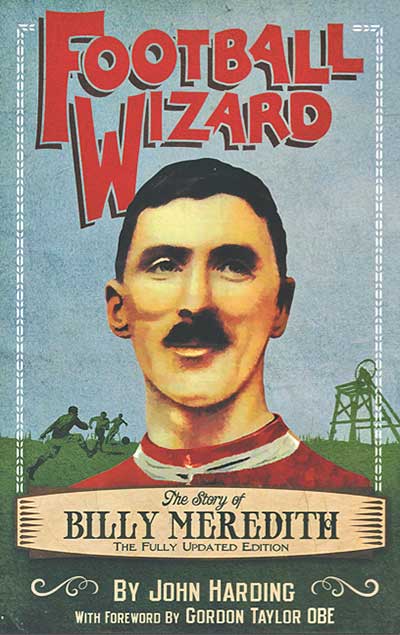

Billy Meredith

The story of

Billy Meredith