The WSC writers’ competition was set up with a legacy left by contributor David Wangerin, who died in 2012. We are now taking entries for the 2015-16 season, and for some inspiration here is the 2015 winner – Adam Deuchars – explaining how he rediscovered his interest in football

Amid the blur of boys in blue and yellow shirts, some in binman orange bibs, the copper hair is easily recognisable. The cacophony of motion is silenced briefly; the boy with the copper hair emerges from the hive of bodies, deftly slipping the ball from his right to his left foot, before placing his shot in to the bottom corner of the goal. The scorer wheels away unsure quite how he has done what he has done only to then hare off down the pitch and throw himself to the ground in celebration. A few of his team-mates pile on.

Once the pile is dismantled the boy emerges again only to engage in some curious victory dance. The parents dutifully patrolling the side of the pitch give me knowing looks. My best response is to shuffle from foot to foot and raise my eyebrows in a “What can you do?” type of way. The coppery haired goalscorer is my six-year-old son. It is another night at training, one of few remaining this season.

My son has an interest and fascination with football that only a six-year-old could maintain. A staggering level of curiosity mixed with a perpetual ability to get muddled by the seemingly arcane workings of leagues, cups, away goals and offside traps. It is a language I know too well and I lose my tolerance at times for the infinite need to explain what seems to be the blindingly obvious. No Manchester City cannot play in the World Cup. No it isn’t unfair that Chelsea are out of the Champions League. No I don’t understand how Steven Gerrard heads the ball with such a small forehead.

Looking back, the exposure to last summer’s World Cup was crucial in this. Sleepy eyed silent mornings were disturbed with requests to know the previous night’s scores, to view the highlights and to stay up late for that evening’s games. It would be wrong to think I am not pleased by this, as I am delighted we have a common interest. The issue is that my interest in football has been on the wane for many years.

I clearly wasn’t as fascinated by the game at the age of six as my boy is. Organised teams and the like didn’t really happen until I was 11. Football stickers, Match magazine and endless kickabouts were perhaps a little earlier at eight or nine. From that point on I would say that my interest, curiosity and pure passion for the game was comparable to that of my son now. This was the early 1980s and football, of course, had a bad public reputation. I never went to matches. In part because we weren’t a footballing family and the sense of matchday tradition and ritual was totally anathema.

The other part was also the threat of violence. There was genuine fear about attending matches which kept me, via my parents, away from games. Despite this my love of and for the game grew and grew. Heysel and Hillsborough unfolded before my eyes yet this didn’t dissuade me. They were curious times and I was steeped in them to the hilt; playing, watching, reading, day in, day out. It wasn’t that I was a good player but I was willing. In my mid-teens I was playing both men’s and junior football. One fortnight when I was 16 I played eight games including two on one day. And I could sustain this as my relationship with the game was deep and involved.

Then, not quickly or even that discernibly, a creeping fatigue set in. I stopped playing 11-a-side in my early 20s, due initially to a combination of the need to work and injury, but I never found my way back. I began to realise I didn’t miss hours of travelling to some godforsaken dog shit smeared patch of grass to endure 90 minutes of threats, abuse and random acts of violence. The players on the opposing teams were little better, of course. In time I could also go weeks without knowing what was going on in the broader world of football. Which was quite a feat given the utter, dripping saturation of the coverage.

Oh how the 18-year-old me would look on in horror and bafflement. That present-day football, the lovechild of Margaret Thatcher and Irving Scholar, was now a mere passing interest, which I dipped in and out of as I chose. That I could cocoon myself away from all of it, content that I was not really missing anything that I could not return to if I wished.

Things have changed again and my son is responsible. Not through the incessant questions along the lines who I like best out of…(randomly pick five Premier League players of your choosing at this point, though one of them has to be Frank Lampard) with follow-up questions where I need to justify my selection. The wilful part of me never allows Frank Lampard at number one.

I am my own worst enemy at times. My son is responsible as there is such simple joy in watching him and his friends play football. Within the shambolic mass of a bunch of six-year-olds there is togetherness and spirit and no little skill at times. By having fun and lumping bits out of one another, they are being together and trying to negotiate all the awkward and difficult bits around sameness and difference. And they do this via football. This is the game I know. It has found me again and I am grateful.

There is a bitter postscript. At the end of May we as parents were informed that the club who host all the junior football were being threatened with eviction by the local parish council. Hallen FC of the Western League Premier Division were being forced to vacate their ground at the Hallen Centre, with Almondsbury Parish Council stating that their financial support for the club was no longer viable. The council is rumoured to be one of the wealthiest in the country, leading to speculation as to what its true intentions are – the land and buildings serve the village of Hallen as a whole.

Losing the facilities would have forced the club to fold, affecting dozens of kids as well as established senior sides. After threats for the club not to hand back the keys, a document was found that secured Hallen FC’s place at the Hallen Centre, which was signed when they gave up their original facilities so that the centre could be built. However at the time of writing no lease had been signed. The footballing future of many could be protected for £20,000 – the amount the council have suggested Hallen need to pay to secure the site. It’s a substantial sum, of course. Unless you are a Premier League footballer or the agent of one.

Illustration by Adam Doughty

Enter the 2015-16 WSC writers’ competition here

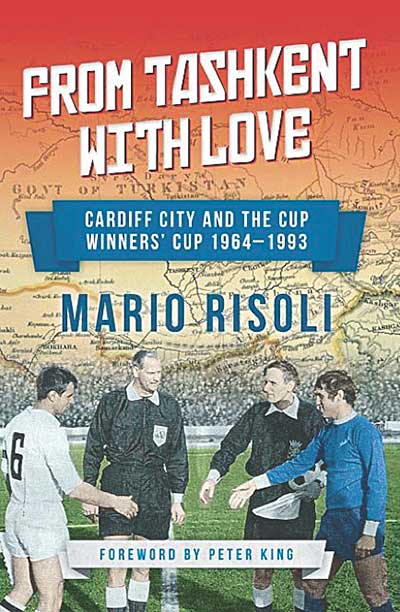

Cardiff City and the Cup Winners Cup 1964-1993

Cardiff City and the Cup Winners Cup 1964-1993 Manchester City have been mocked for low attendances but the criticism is a cheap shot which ignores glaring facts about their supporters, states Matthew James

Manchester City have been mocked for low attendances but the criticism is a cheap shot which ignores glaring facts about their supporters, states Matthew James Moving to the NASL was a culture shock for many British pros in the 1970s – an extract from

Moving to the NASL was a culture shock for many British pros in the 1970s – an extract from