Search: 'Brazil'

Stories

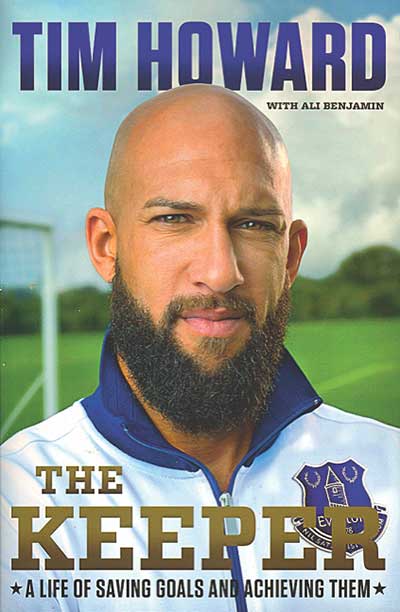

A life of saving goals and achieving them

A life of saving goals and achieving them

by Tim Howard with Ali Benjamin

Harper Collins, £18

Reviewed by Ian Plenderleith

From WSC 338 April 2015

Twice in two pages I laughed out loud during this otherwise unfunny book. When a young Tim Howard arrives in England to play for Manchester United, he calls his compatriot Kasey Keller in London for some advice. “Well, Tim,” says the older, wiser sage of White Hart Lane, “I guess my advice to you would be this: make as many saves as you can.”

Just seven paragraphs later, Howard recalls his senior debut for United and captain Roy Keane’s pep talk before the 2003 Community Shield game against Arsenal. “Just pass it to a red shirt, guys. It’s as simple as that: take the ball and pass it to another player in red.”

The problem with reading footballers’ autobiographies is that you rarely learn anything new. Not about the game and not about the player. As David Foster Wallace wrote in his review of tennis star Tracy Austin’s life story, such books are “at once so seductive and so disappointing for us readers”, because the player is only equipped to “act out the gift of athletic genius”. If they were able to articulate that gift, they probably wouldn’t possess it

at all.

That’s where the ghost writer comes in, but they can only work with what they’re given. Howard’s flat account of his life is imbued with the kind of sentimental journalese that signifies a second pair of hands. His ability to overcome Tourette’s syndrome is interesting and admirable, but is not compellingly told because the writer fails to get inside Howard’s head. Either the goalkeeper wouldn’t let her in, or she chose not to go there. While there may have been good reasons for that, it fails to lift the book above its absolutely ordinary level. Instead, the tension is stressed on the Belgium v US World Cup round of 16 game in Brazil, with interludes between each chapter taking us through the action. This was of course a heroic performance by Howard, but we know how it ended. The US lost. It was just last summer, remember?

In fact the most intriguing thing about Howard’s book is how he dodges the issue of his failed marriage. For the longest time we hear only wonderful things about his wife, Laura. Then while in South Africa at the 2010 World Cup Howard blithely springs it on us that he doesn’t miss her any more. He blames the “suspended reality” of life as a football player, “where we retreated… into a kind of grade [junior] school mentality”. His previously extolled faith in God is suddenly of no help. Being “addicted to my job” is the closest we come to learning why he gets divorced from the seemingly perfect mother of his two children (I really hope Laura got a better explanation than that).

Such withheld integrity makes this kind of book a bust. It exists to sell, not because Tim Howard wants to share his world with you. If there’s no narrative, you should stick to making as many saves as you can.

{youtube}Sp3A54Hm66g{/youtube}

edited by Jethro Soutar

and Tim Girven

edited by Jethro Soutar

and Tim Girven

Ragpicker Press, £10

Reviewed by Nick Dorrington

From WSC 335 January 2015

The Crónica is a Latin American literary form, somewhat akin to the output of the new journalism movement of the 1960s and 1970s, in which the author involves themselves, to some degree, in the story. Written from a bold and engaging first-person viewpoint, it is a form that is the subject of a number of dedicated magazines across Latin America.

It is through the medium of the Crónica that this collection explores the football and society of a region in which a team bus is shown more deference than an ambulance in traffic, where villagers gather on a hillside to get the best possible signal for the radio broadcast of a match and where entire cities can be brought to a halt by an important fixture. These entries are supplemented by a book extract in similar style and three short stories.

The standard varies a little from piece to piece but the overall quality of both the writing and translation is to be applauded. Authors from across South America, plus two from Mexico, have been included, writing on subjects as varied as a prison team in Argentina, a Latino immigrant league in New York and a team of transvestites in Colombia. The rare missteps occur when the focus is on well-known subjects such as Alcides Ghiggia or Romário.

One of the most interesting entries is by the Peruvian writer Marco Avilés. It tells the story of the women’s football team of a high Andean village where no Spanish is spoken and the comforts of modern society are not to be found. The women travel down to the nearest developed city to take on the local team in a match that Avilés bills as a battle of ojotas (rustic flip-flops) versus trainers; ancient tradition against globalisation.

The changing face of football is masterfully described in a wry short story about an elderly man denied access to a stadium due to his failure to produce a shop loyalty card. “Purchasing power is all that matters,” a steward tells him as the man fruitlessly describes the various triumphs and defeats he has witnessed in his many years in the stands.

The best pieces in the collection are those about people who for one reason or another stand on the margins of mainstream society. We sometimes forget that football, in its most basic form, can act as a unifier for communities, or provide a platform for those whose voice is rarely heard. This theme is beautifully summarised in the final entry, a short story by Vinicius Jatobá that provides a fictionalised account of the genesis of Brazilian football and the emergence of Leônidas da Silva in the docks of Rio de Janeiro.

Laced with local patois and references to the art, food and history of the region, the book is, at times, a challenging, even daunting read. Explanatory footnotes would have been a welcome addition. Yet it is still an enlightening and ultimately rewarding excursion into the football and culture of Latin America.

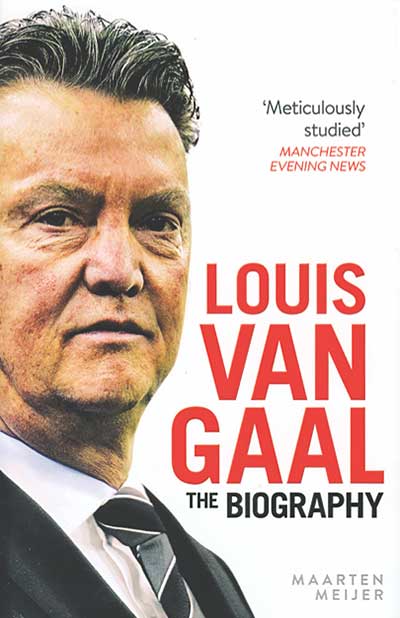

by Maarten Meijer

by Maarten Meijer

Ebury Press, £14.99

Reviewed by Joyce Woolridge

From WSC 333 November 2014

“When you traced the roots of the successful teams at the 2010 World Cup, every clue pointed back to one man: Louis van Gaal.” Maarten Meijer’s carefully researched biography is not afraid to make big claims for its subject. While conceding that credit is also due to Joachim Löw, Bert van Marwijk and Vicente del Bosque, Meijer argues that the controversial coach’s influence, through his work at Bayern Munich, Ajax and Barcelona, principally shaped the personnel, playing style and tactics of three of the four semi-finalists in South Africa. The book was finished before Holland’s unexpectedly barnstorming campaign in Brazil this summer and Germany’s victory (albeit also the Spanish collapse), which might serve as additional support for Meijer’s thesis on the extent of Van Gaal’s impact on European football.

It remains to be seen whether Van Gaal’s tenure at Old Trafford will provide further proof of the genius of “one of football’s most gifted architects”. The brief coda which deals with his United appointment, while stating the obvious that the £200 million “war chest” supposedly on offer “may have been an additional attraction” for Van Gaal, goes on to make the equally obvious observation that “he needs a new defence and a new midfield”. The final paragraph speculates that United will be his last management job and “he will want to go out with a bang, knowing that this is how he will be remembered not only in Manchester but in the entire world of football”, but reserves judgment on what sort of explosion Van Gaal will cause.

Meijer’s primary purpose in writing this heavyweight, thoughtful study, following his two previous biographies of Dick Advocaat and Guus Hiddink, is to balance the media caricature of Van Gaal, the crude stereotype of a lumbering, bombastic, dictatorial ex-PE teacher, ranting at the press and indulging in eccentric and bizarre behaviour (trouser-dropping, self-penned, excruciating poetry-reading) occasionally deemed akin to madness. Like Alex Ferguson, Meijer argues, Van Gaal is a man so out of style that he has become a “poster boy for the old-school, omnipotent, teacher-knows-best style of management”. So often following the boots of Johan Cruyff, as both player and coach, he has been cast as the anti-Cruyff, whereas his work should often be seen as complementary, Pep Guardiola’s all-conquering Barcelona being an amalgam of the philosophy of both coaches. In consequence there has been serious underestimation, if not misrepresentation, of Van Gaal’s talents and achievements. The real Van Gaal is more flexible and democratic in management and tactics, more humane and caring one-to-one.

Not that Meijer’s generally sympathetic account whitewashes over Van Gaal’s failings, or the barrage of criticism he has received, dealing with both at length. The most entertaining chapter predictably concerns Van Gaal’s fractious relations with the press. As boss of Ajax, he received a deliciously pompous letter from the Dutch Reporters’ Association, complaining press conferences were being “disgraced by vulgar shouting matches. This aggressive approach perhaps guarantees success with young, docile players but it is inappropriate at a press conference at which adult people are present”. At the next conference, in classic teacher mode, he asked those who signed it to put up their hands. Not one “adult” person did.

As a compatriot, Meijer could perhaps be forgiven his own excursions into national stereotypes. Van Gaal, he says, must be fundamentally understood as a typical Amsterdamer and Dutchman – hardnosed, unshakeably convinced he is right, highly focused, pig-headed, difficult to get along with and rebellious. Or as one journalist put it more succinctly: “An asshole, but certainly a competent asshole.”