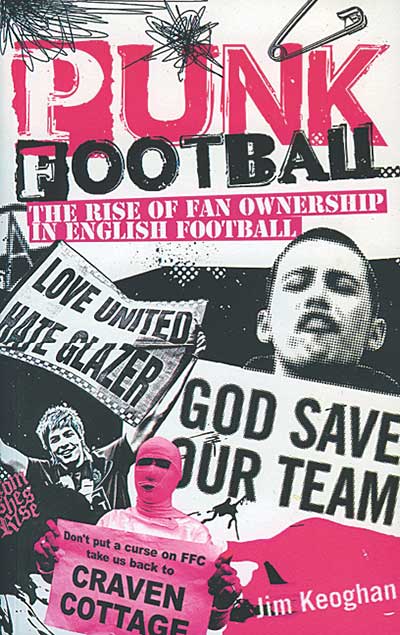

The rise of fan ownership in English football

The rise of fan ownership in English football

by Jim Keoghan

Pitch Publishing, £12.99

Reviewed by Tom Davies

From WSC 332 October 2014

It is surprising that the rising supporter activism of the past three decades – from the inky anger of 1980s fanzines to the thoughtful campaigning on governance and club ownership of the supporters’ trust movement – has not been more widely chronicled. Jim Keoghan has made one of the few readable stabs at drawing all these stories together in Punk Football, which traces how fan protest has shaped the game in recent times, including where it has failed and the formidable forces it is up against.

With a useful introductory section looking at the history of how English football and its clubs came to be organised as they are, with the transition from members’ clubs to private companies that accompanied the rise of professionalism and mass spectatorship at the back end of the 19th century, Keoghan rightly places the structure of clubs at the centre of the story. So developments such as the abolition of the maximum wage, the formation of the Premier League and Bosman are given full acknowledgement.

Many of the stories here will be familiar enough – the anti-bond scheme protests at West Ham United in 1991-92, the fight to stop Rupert Murdoch’s takeover of Manchester United, the formations of FC United and AFC Wimbledon, meltdowns and fights back at Brighton, York, Portsmouth and elsewhere – but Keoghan has done an impressively exhaustive research job in talking to key protagonists about how the idea of supporter control, at club level if not, alas, at national administrative level, has taken root.

He’s not blind to where things have gone wrong – a chapter is given over to failures of varying degrees at places such as York, Notts County and Stockport, though it is debatable whether we need the one on where directors have done right by their clubs. Many of Keoghan’s interviewees also concede the underlying tension between those fans who care only about results and those prepared to be more political about it.

He looks abroad too, at the strengths and occasional weaknesses of fan ownership in Spain, Germany and Sweden, acknowledging the underlying economic and political explanations for these developments, such as the much later arrival of professionalism in Germany. That many fans in Sweden have rallied to the defence of their own model despite a lack of big club success in Europe that might have prompted a frantic dash to turbo-charged commercialism is also noteworthy.

At times it’s unclear whether Keoghan, an Everton fan, is writing for an uninitiated or deeply committed audience – do we really need the Bill Shankly “life or death” quote, the introductory blurb about the nature of fan loyalty or the apparent astonishment that a League Two game is as passionate and committed as a top Premier League encounter? In light of this, editing errors that have Rochdale and Exeter at points given the suffix “United” to their club names jar. The absence of any significant discussion of Hillsborough – the single most momentous event around which the late 1980s/early 1990s fanzine and activism boom took place – also seems curious.

The phrase “Punk Football” itself, too, woven liberally through the text, also feels a little forced. If we’re going to run with music analogies, supporter activism is now deep into its post-punk phase, the initial outpouring of unfocused anger and energy having made way for something much more creative and influential. But these quibbles do not detract from the fact that this is an important book, well balanced and accessibly written, and a very handy primer for those looking for an easy account of how organised fandom has evolved, and what they themselves can contribute. To run with the punk metaphor and paraphrase the famous 1977 fanzine rallying call, this is one football club’s story, this is another, this is a third – now run your own one.

Plans for Ashton Gate include installing rail seats but Bristol City will not benefit unless the law changes,

Plans for Ashton Gate include installing rail seats but Bristol City will not benefit unless the law changes,  Both Cambridge clubs United and City have seen their requests for new grounds denied, writes

Both Cambridge clubs United and City have seen their requests for new grounds denied, writes  Trains are an important mode of transport for fans but

Trains are an important mode of transport for fans but  They don’t make them like him any more

They don’t make them like him any more