The triumph and tragedy of football’s forgotten pioneer

The triumph and tragedy of football’s forgotten pioneer

by Dominic Bliss

Blizzard Books, £10

Reviewed by Jonathan O’Brien

From WSC 340 June 2015

Erno Erbstein is a deeply niche subject for a book, the first to be published by Jonathan Wilson’s quarterly which has won a deserved reputation for quality output over the last few years. Though the incident in which Erbstein perished – the 1949 Superga air disaster that wiped out the entire Torino squad – is one of the defining moments of Italian football history, his own story has slipped through the cracks of memory until now. And though he came from the same central European Jewish coaching lineage as Hugo Meisl and Bela Guttmann, he’s far less well known than either of them (as the title of this book implies).

Five years in the writing, Dominic Bliss’s biography is a hugely well-researched and elegantly written study of a man whose life was punctuated with innumerable dangers and hardships (he served briefly in the First World War and later survived the Holocaust). Perhaps unsurprisingly in view of this, as a player Erbstein gained a reputation for a robust style: a particularly poor challenge on an opponent during a match was one of the two reasons he got out of Budapest in the 1920s. The other was the dark shadow of encroaching anti-Semitism.

In 1928, Erbstein began coaching in Italy, where he assembled a series of tightly organised teams from seemingly unpromising materials, like a proto-Otto Rehhagel. He put the emphasis on quick-fire passing and subjected his players to relentless drills, so that they would be able to pass to each other in their sleep. And the results, initially unspectacular, soon flowed easily: he got the tiny Lucchese club up to a seventh-place finish in Serie A, for example. “He conceived a mode of football 30 years ahead of its time,” says one Sardinian journalist whose father was in the Cagliari youth team while Erbstein was manager there.

Sadly, like so many other Jews, Erbstein spent all too much of his life frantically moving around Europe in search of sanctuary. Benito Mussolini’s 1938 Manifesto of Race forced him to flee again, this time back to Hungary, where he went into business with his brother. He narrowly saved his wife and daughters from death at the hands of the Nazis by utilising one of his innumerable connections (a story recounted in gripping detail here by his daughter Susanna, who’s now in her 80s). Meanwhile, he himself, along with future Benfica manager Guttmann, jumped off a train taking them to a concentration camp in Germany.

After the war, Erbstein came back to Torino, where he had been coaching before Mussolini’s reign of terror. They had won the league twice in his eight-year absence, but now he and club president Ferruccio Novo made them an even better team who cruised to two more championships. Had the European Cup existed at the time, they would undoubtedly have won it at least once. And then, on May 4, 1949, came Superga. This is a sad book in many ways, unashamedly esoteric, and also a fine one.

The rise and fall of Carson Yeung

The rise and fall of Carson Yeung Everpresent since 1968 – an incredible journey

Everpresent since 1968 – an incredible journey Football’s journey through the English media

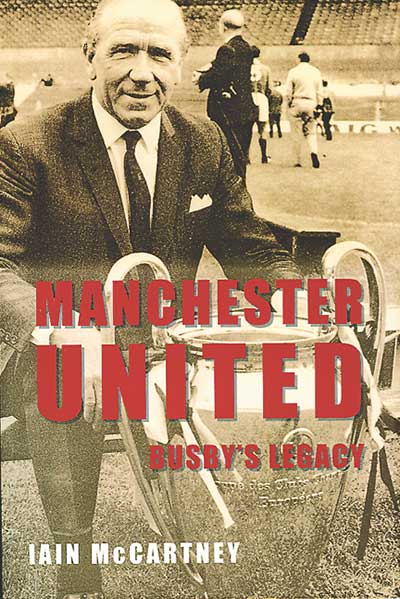

Football’s journey through the English media by Iain McCartney

by Iain McCartney