De Coubertin Books, £16.99

Reviewed by Tim Springett

From WSC 377, July/August 2018

Buy the book

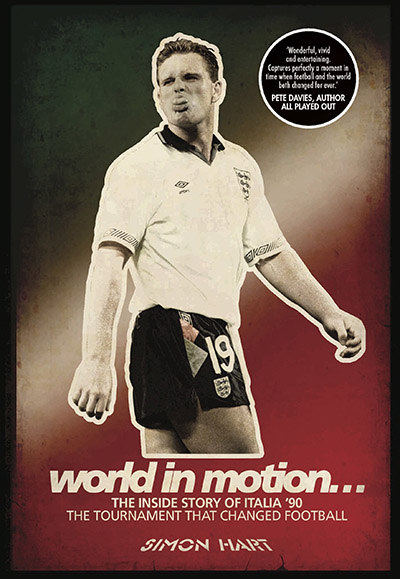

If All Played Out by Pete Davies is viewed as the definitive story of the 1990 World Cup, Simon Hart’s World In Motion is its worthy younger sibling. This is no rose-tinted nostalgic view of the tournament – no attempt is made to conceal its status as the worst tournament in the World Cup’s then 60-year history. While the book’s description of Italia 90 as the tournament that changed football might seem to imply that no other World Cup has done this, the 373 pages build a convincing case for the assertion.

Hart places the 1990 tournament into its historical context; a year earlier, communist regimes in Romania and Czechoslovakia had collapsed, then before the year’s end West and East Germany had reunited. The fall of the Soviet Union, the peaceful separation of Slovakia from the Czech Republic and the violent fragmentation of Yugoslavia followed. Hart interviews an impressive roster of key players – and allows them to tell the story. Roger Milla confirms how his inclusion in the Cameroon squad owed much to the intervention of the country’s president, while a meeting with Toto Schillaci underlines his status as one of the most unlikely World Cup heroes. Meanwhile native Berliner Pierre Littbarski speaks of watching a “miracle” on television as the Berlin Wall fell.

One of the most intriguing accounts is told by Czech striker Ivo Knoflicek. Spirited away from a training camp in Hanover with a promise of a contract with Derby County, he eventually arrived at the Baseball Ground on a bought Bolivian passport but never received the necessary international clearance to turn out for the Rams, thanks to FIFA rules covering defectors from behind the Iron Curtain. Then the ushering in of democracy by Vaclav Havel paved the way for Knoflicek to rejoin the national team. Hart even secures an audience with Sepp Blatter to discuss the changes to the offside rule, the backpass ban and automatic red cards for professional fouls that were introduced in order to discourage the defensiveness and foul play that marred the tournament.

The action on the pitch is also considered, particularly England’s semi-final defeat on penalties to West Germany. It brought about a transformation in attitudes at home towards football – not least from the British government which, in a time of political crisis, saw an opportunity to reflect the positive mood pervading the nation onto itself. English clubs would be welcomed back into European club competitions, even though – as Hart points out – hooliganism continued in the centre of Turin after the match. For better or for worse, the game in England in particular would never be the same again.

The only disappointment for readers in the UK is that, among the detailed accounts of the impact of Italia 90 in the US and the United Arab Emirates, there is little analysis of Scotland. Italia 90 was the Scots’ fifth successive World Cup; they have qualified once since, in 1998. Maybe an examination of the decline will be the subject of Hart’s next book.

Nevertheless, it succeeds in being both objective and passionate, diligently researched but never dry or heavy. One of the best works that any World Cup has inspired.