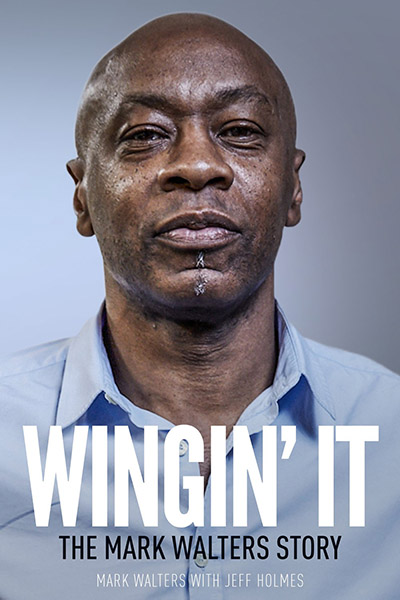

Pitch Publishing, £18.99

Reviewed by James Marsland

From WSC 385, April 2019

Buy the book

Mark Walters was never one of the stars of British football, and yet nor is he gifted with the kind of cheery obscurity that means he can amusingly rail against the game from its foothills. Being caught between the two may suggest a worthy plod through youth teams, professional contracts, injury, retirement and property development, but Walters’ story contains a lot more than it might suggest.

To the uninitiated, Walters was a winger with Aston Villa, Liverpool and Rangers, a trinity which would make most publishers decide that this was worth a punt. But he was also one of the first black players in Scotland and had the unenviable job of being one of the footballers who had to stake their claim in the game at a time when it was unremittingly, hatefully racist. And he also came within a hair’s breadth of being sexually abused by paedophile Ted Langford, a former Villa youth scout jailed for sexual offences in 2007.

Our collective understanding of racism in sport has been shaped by numerous testimonies from articulate sportsmen and women who, with infinite patience, have explained how numerous incidents made them feel and, often, how it blighted their careers. With paedophilia in sport, there is still an urge to pretend it no longer happens when everything suggests otherwise. It is to Mark Walters’ immense credit that he tackles the subject head on. There is no evasion, and no cosy euphemism. He sees with huge candour what the implications were for team-mates who were less lucky than him and describes, in tragic detail, how Langford was able to exploit people’s casual dismissals to ruin lives.

And he also sets in an immensely realistic context. With someone who was later convicted as a serial sexual abuser in his immediate environment, Walters is focused only on first-team football with Villa. This is what every other starstruck and single-minded young footballer would have done and it was clearly the responsibility of people with an infinitely greater duty of care than a teenage Walters.

His time in Glasgow is the second moment when this autobiography is raised into something that repays closer attention. He faced the full spectrum of hate from the language to the missiles. Instead of brushing this off, cheerily invoking Cyrille Regis as he does so, he talks about its effect on him as a footballer and as a man, of attempting to perform in front of several thousand people intent on shaming you into substitution. The Hearts fan who writes to him, ashamed at the behaviour he had demonstrated when Walters came to Tynecastle, and support from his team-mates are rare highlights in a period described with brutal honesty.

Football autobiographies are seldom a place for great and timeless wisdom, but Mark Walters and his co-writer, Jeff Holmes, have lifted this above the multitude. The honesty is leavened with humour and self-deprecation, and the tone throughout is conversational, but there is candour and insight that does them both credit, and passages that deserve a much wider reading.