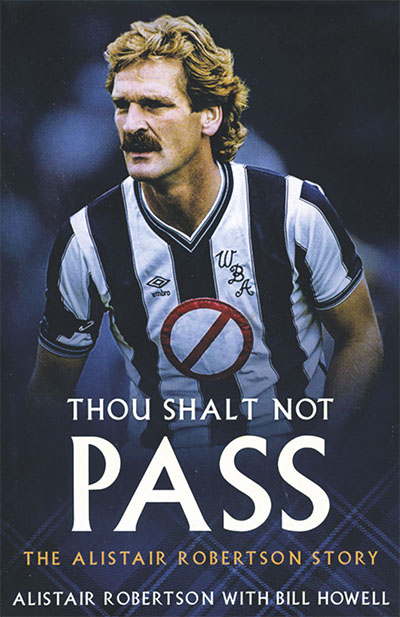

by Alistair Robertson with Bill Howell

Pitch Publishing, £18.99

Reviewed by James Baxter

From WSC 375, April 2018

Buy the book

There are already plenty of accounts of West Bromwich Albion’s exciting late 1970s/early 1980s era, yet Alistair Robertson deserves to get his story into print. One half of a fine central defensive partnership alongside John Wile, Robertson is second only to Tony Brown in Albion’s all-time first-team appearances chart (626, between 1969 and 1986). He is also one of very few players who can claim a place in the affections of both Albion and Wolves fans, having played a significant role in the latter’s recovery from their mid-1980s crisis.

The book was ghost-written by journalist Bill Howell, an Albion fan who, “to his horror”, has also covered Aston Villa and Wolves for the Birmingham Evening Mail. It will, in the main, satisfy Albion fans’ preconceptions regarding managers. Robertson is warm towards Alan Ashman, the man who gave him his debut in 1969, and generous in his praise of Johnny Giles and Ron Atkinson. He didn’t get on with Don Howe, and believes Bobby Gould (the player) was recruited to be Howe’s dressing-room spy. Even so, Howe is described as “ahead of his time” as a coach, and Robertson is happy to quote former team-mates ready to speak up for Gould. Only Ron Saunders, who ended Robertson’s Albion career, is spoken of with unmitigated contempt.

Many of the stories too, such as that of the “sea of green and yellow” at Boundary Park as the club won promotion under Giles in 1976, or Cyrille Regis knocking Wile over to power home a header on his first day at training, are established parts of Albion folklore. New insights are added to familiar tales. Robertson gives the obligatory account of Albion’s 1978 tour of China, but admits that he would love to see the country again, as a mature traveller rather than as an easily bored young footballer.

Robertson’s fair-mindedness extends to his judgements of other footballers; the likes of Jon Purdie, David “Digger” Barnes and Floyd Streete in the struggling Wolves team he joined have their talents analysed as seriously as Regis, Wile or Brown at Albion. With two divisional championships and the 1987 Football League Trophy, Robertson did at least win honours with Wolves. Conversely, he partly blames Albion’s failure to win a trophy during his time at The Hawthorns on his own tendency to make mistakes on big occasions.

Robertson was never seriously in contention for the Scotland national team, and there is a sense that this remains his biggest regret of all – considering the many affectionate portraits of his upbringing in a small village near Linlithgow, for his family’s sake as well as his own. Scotland fans might see symptoms of the national side’s decline in the fact that they were able to overlook Robertson throughout his career, yet have recently had to field players such as Grant Hanley and Russell Martin in central defence. The book leaves the impression, however, that Robertson would not be the type to offer such observations himself.