Biteback, £20

Reviewed by Huw Richards

From WSC 366, August 2017

Buy the book

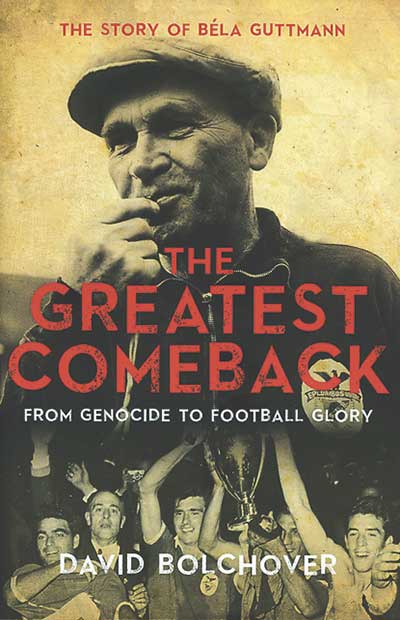

If Bela Guttmann had never done anything but coach football teams, achievements such as managing Benfica’s two winning European Cup campaigns would justify a full-dress autobiography. Guttmann did much more. As author David Bolchover notes of a 2013 survey of experts rating him the ninth greatest coach of all time: “I did scour the life histories of the top eight, but as far as I could make out, not one was hunted down by the Nazis, had their family murdered or escaped from a forced labour camp. Moreover the top eight all came after him. It was he who blazed the trail.”

This is the “life and times” model of biography with a vengeance. In the index “Hogan, Jimmy” and “Honved” are separated by “Holocaust”. Each chapter is prefaced by a vignette, almost invariably grim, from Jewish history.

{loadposition user 1}

Not the least of Bolchover’s achievements is filling in Guttmann’s wartime existence, a speculative void in previous English-language accounts. He uncovers several months hidden in a Budapest attic followed by that escape from a forced labour camp in a group also including Erno Egri Erbstein, later to coach Il Grande Torino, who won five consecutive Italian titles, and perish with his team at the Superga air crash in 1949.

Guttmann’s was a life devoted to football – Bolchover suggests that his near-suicidal return to Nazi-occupied Austria in 1938, after a spell coaching in the Netherlands, reflects an inability to do without the game – but subject to the fates which engulfed European Jews in the first half of the last century. And as much as this is a portrait of a remarkable, brilliant, cantankerous human being, it is a lament for a lost world, “a vibrant Jewish Europe which no longer exists” whose achievements included an immense contribution to the brilliant football played in Austria and Hungary between the 1920s and 1950s.

Guttmann played for eight different clubs and coached 20, living in 14 different countries – as Bolchover notes an authentic “Wandering Jew”. It is a picaresque tale populated by characters such as Dutch referee and resistance hero Leo Horn, Erbstein and Dezso Solti, who later fixed referees for Italian teams in Europe, and was the owner of and passenger in the car which Guttmann, who had no licence but was “driving at great speed in central Milan”, killed a young Italian in 1955, an act which merited but escaped imprisonment.

There were potential points of stability. The chapter on his time as a player with the remarkable Hakoah club, first professional champions of Austria in 1924-25, by itself justifies the book. Late in life he returned to Vienna, fulfilling Jonathan Wilson’s description of him as “the last of the coffee-house coaches” by haunting the Cafe Europa on Karntnerstrasse. And Bolchover suggests that, partner in a lucrative speakeasy, he might have remained in the US where he was playing for New York Hakoah, but for the crash which destroyed his savings in 1929.

At times like that Guttmann was compelled to wander by circumstances. But Bolchover shows that he was far more compelled by temperament, his coaching career a cycle of brilliant starts followed by fallings-out. Only once, at Benfica, did he make it to the third season he regarded as “hell”. There is a foretaste of José Mourinho, but with critical differences – Guttmann was committed to attacking football and believed in young players.

His wanderings made him a transmission belt for that philosophy, most famously in Brazil where World Cup-winning coach Vicente Feola credited him with tactical innovations underpinning the breakthrough in 1958. Bolchover concurs with Wilson’s judgment that it was a matter not so much of tactics as style, Guttmann infusing 4-2-4 with purpose much as his Hungarian compatriots had taken the flowing-for-its-own-sake Viennese game and given it an attacking edge.

Bolchover locates Guttmann clearly not only within that brilliant Mitropan tradition, but in the wider context of Jewish experience. He notes that Guttmann’s Jewishness scarcely features in his first autobiography in 1964, but argues that his identity was fundamental to what he was and did. Not everyone – least of all some Jews – will accept an implicit conflation of the state of modern Jewry with the state of Israel, but the context is sensitively and lovingly drawn. A remarkable life has the thoughtful, passionate biography it has long deserved.