Not all footballers crave the spotlight. James Wilson has realised that Faustino Asprilla is happier away from media attention

Not all footballers crave the spotlight. James Wilson has realised that Faustino Asprilla is happier away from media attention

Colombia do not play their home games in the capital, Bogotá. Instead they have adopted Barranquilla, a coastal city of tropical languor, as their base. It is a welcoming city. Gabriel Garcia Marquez once lived in a brothel here. Outside the Dann, the nondescript suburban hotel where the players were staying before flying off to Paraguay for the World Cup game, a banner strung across the street said: “The Colombian squad is here.” So were a lot of military police.

I spent three days in Barranquilla and did as the large body of Colombian journalists did – hung about the hotel lobby in search of someone, anyone, to talk to. I gave four radio interviews. Each morning and afternoon the players would appear in the lobby in their football kit – it must be nice to be able to walk around luxury hotels in your football boots – and would try to spend as little time as possible with journalists and fans before climbing into the bus which took them to training. Then we would climb into our rickety cars and jeeps and chug off in pursuit of the bus to the training ground, where we would wait for things to happen. Once a pop star, Jorge Onate, turned up, so everyone interviewed him. It was 8am and he looked as if it was a bit early for him. Another time one of the coaches walked over and said: “Can’t trust you folk round here with anything.” Someone had stolen some of the goalkeeper Miguel Calero’s kit. Calero appeared for breakfast the next day in his swimming trunks.

Asprilla is normally the last player to appear on the pitch and he was invariably the last to show up for the bus – socks rolled down, mobile phone in hand, no sign of any football boots but with his feet stuffed into sandals. His standard expression was the familiar, scared, ‘don’t hit me’ one, as if he were about to cry. After training, while fans and press clustered around, Asprilla would be the first back on the bus.

Asprilla seems to be granted a large degree of leeway within the Colombian squad. On the first morning I watched training, while the rest of the players began their warm-up, Asprilla sat on the treatment table looking pained. But as soon as a camera crew came over to talk to him, he went over to join in the game. That lasted two seconds – literally. Then he went to have a play fight with one of the coaching staff. “He’s being difficult,” said the TV crew’s reporter. “He says he’s got a headache.”

The next day Asprilla was still apparently troubled by some sort of mysterious injury. He lay on the treatment table, with the sporting director of the Colombian Football Federation, Gustavo Moreno Jaramillo, stroking his head and rubbing his ear. Asprilla finally got off the treatment table and wandered over for a chat with the coaches. He still didn’t have his boots on. Then as the players all sat gathered around the coaching staff, apparently taking instructions, Asprilla got up and walked off, vainly pursued by his friend, goalkeeper Farid Mondragon, and Moreno Jaramillo. Leaving his boots behind, he walked out of the stadium. The training session went on, culminating in a long chat in the centre circle, the players lazing around with towels on their necks. It looked like a public show of bonding. Finally they went off laughing to the team bus, where Asprilla had been sitting by himself for nearly an hour.

The Colombia coach, Hernan Dario Gomez, played down the incident. He plays down everything with Asprilla. Asprilla played under Gomez at Nacional before he went to Italy, and the two, outwardly chalk and cheese, have a fine chemistry. Gomez, portly and moustachioed, told me himself that they were like father and son. In 1993, when Asprilla walked out of the Hotel Dann after being dropped from the team, and was told he would never play for Colombia again, it was Gomez who got him reinstated.

When I asked Gustavo Moreno Jaramillo about Asprilla, the first words he said were: “He’s mad.” Then he thought a bit more. “He brightens up the whole team. Before he arrived we were all glum. Now he’s here and he puts everyone in a good mood.” When the squad met up before the previous game, he told me, Asprilla sang in the lobby of the Hotel.

“Asprilla bought a heart machine, in 1993, for the children’s hospital in Barranquilla,” one journalist told me. “He just wrote a cheque out in the lobby of the hotel here. He gave it to a nun. I was here when he gave her the cheque. It was at half past two,” he added.

There was also much speculation about the divorced Asprilla’s relationship with a Colombian actress and model named Lady Noriega, the mention of whom induced much blowing out of cheeks and jealous shaking of heads among most men I talked to. Lady Noriega had just released a pop record which had been well received. In one magazine she was included in a list of Colombia’s worst dressed women of 1997, pictured in a spotted fur three-piece ensemble of jacket, trousers and push-up bra. “Personifies the worst nightmares of Cruella de Vil,” was the expert’s judgement. “A Dalmatian in a bra!” Lady Noriega has apparently visited Asprilla in Newcastle, though presumably she packed something warmer than the dog outfit.

In Barranquilla I kept asking Asprilla for a chat but it was generally ‘later’ or ‘tomorrow’. I finally managed to speak to him on the eve of Good Friday. Earlier I had accompanied his teammate Anthony De Avila and a television crew to the nearest church, where De Avila spent some time in positions of Catholic devotion for the benefit of the cameras, gawped at by several hundred fellow adherents. De Avila is strongly religious; when he played for America, the Cali club whose shirt badge depicts a devil, he covered up the badge before playing.

De Avila, a quiet, amenable man, now plays for New York Metro Stars in the United States. “It’s a very English style,” he said, wrinkling his nose. “The ball’s in the air the whole time.” De Avila is about five foot four.

We needed a police escort back to the hotel, where De Avila struck up a conversation with a pair of evangelical protestants. A few minutes later Asprilla and Mondragon were dragged over to their table, one of the evangelicals saying: “There’s a lady here who would like a word with you.” It was obvious they were being summoned for some spiritual guidance. The group sat deep in conversation for some time, and bowed heads in prayer.

So by the time I asked Asprilla for a few words he was perhaps dwelling on spiritual matters, or just pissed off; certainly a few words were all I got. Yes, he liked it at Newcastle, where he was able to live quietly; no, it was not so different from Italy. It didn’t matter that he didn’t get the chance to get back to Colombia much – he could relax and ride his horses in the holidays. I had thought he would feel like a fish out of water at Newcastle, but evidently not. “I don’t need to be surrounded by Latins to feel happy. What is important is what happens on the pitch. That’s what I’m employed for,” he explained. And that was about it before he got up to head for the lifts. I barely had time to ask him about the little cameo I had just seen. Was religion important to him? He nodded sagely. “It’s always important to pray,” he said. “Especially on a day like this.”

So I asked the two evangelicals about their meeting. “I saw you praying with Faustino Asprilla – I didn’t know he was very religious.”

One of them looked darkly at me. “He’s not,” she said rather shortly.

“What did you say to him?” I asked the other one.

“I told him that, yes, he has his money and fame, but fame will disappear,” she replied. “But God is forever, and I told him he should remember that.”

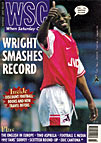

From WSC 128 October 1997. What was happening this month