Coronet, £17.99

Reviewed by Charles Morris

From WSC 391, October 2019

Buy the book

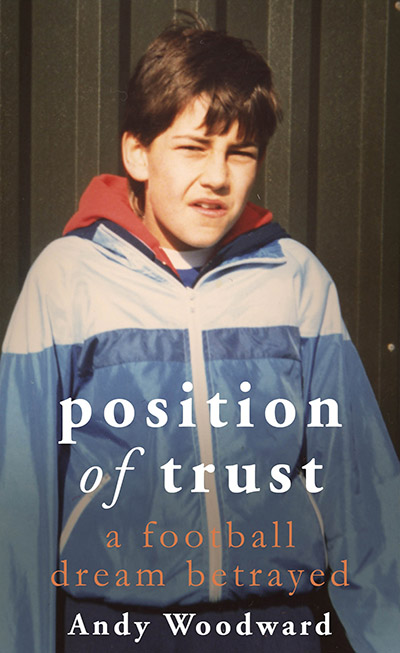

The whistle-blower of British football has written a harrowing but engrossing slow burn of a book that ultimately explodes with huge significance for the game worldwide. Andy Woodward is the ex-player who in 2016 revealed his sexual abuse by youth coach Barry Bennell, and thereby helped expose widespread child abuse throughout the sport as hundreds of other victims followed him in coming forward.

Woodward’s memoir courageously details Bennell’s grooming of him and his family, and the multiple rapes he and others suffered while a junior player at Crewe Alexandra. He is also extraordinarily honest about his resulting disastrous life, including four divorces and a police career that ended with dismissal for misconduct after an improper relationship prompted a false rape accusation.

Tragedy has indeed been his family’s curse. His grandfather, a navy mechanic, perished when his submarine collided with an oil tanker in 1950. His 22-year-old aunt was murdered in 1970 by, in an astonishing coincidence, Bennell’s cousin. Bennell himself compounded his cruelty by marrying Woodward’s older sister, Lynda. And their father Terry died of motor neurone disease, having lived with the shattering knowledge of his son’s abuse by a man he had trusted and taken into his family.

Ghostwriter Tom Watt maintains a conversational style that briskly propels the story, as well as explaining the complex psychological reactions of victims. Bennell not only coerced a ten-year-old Woodward and others with a combination of fear and control of their dreams of becoming professional footballers, he also reinforced feelings of shame and guilt to maintain their silence. The principal long-term effect on Woodward has been post-traumatic stress disorder, which eventually destroyed his promising football career.

The abuse also left him confused about his sexuality and unable to engage in intimate relationships. His womanising was a means of gaining sexual reassurance, but he does not spare himself regarding his behaviour. “My past explains what happened, perhaps,” he writes. “But it can’t ever justify it.”

Football – whose culture he describes as “macho, secretive and controlling” – emerges badly from this story. Only Stan Ternent and Neil Warnock, his managers at Bury and Sheffield United who made allowances for his trauma, earn praise. He accuses Crewe officials of either ignoring or being in denial about Bennell’s behaviour, which at the time was discussed openly by Crewe players and opponents.

Woodward has doubts about the sincerity of the FA’s response to the general scandal and how much its delayed inquiry by Clive Sheldon QC will reveal. His full evidence to the inquiry of his six years of abuse while at Crewe, for instance, was reduced to only three paragraphs when returned to him for checking.

Just when the reader thinks they cannot be shocked further, Woodward tells of a visit to Brazil to speak to young players about abuse. “The scale of the problem in Brazil is mind-blowing,” he writes, because football is often the only escape from poverty and parents are tempted to entrust children to anyone. The horrific thought follows that this must also be the case in many other countries. This book should be compulsory reading for every sports official concerned with juniors – and certainly for every football club chairman.