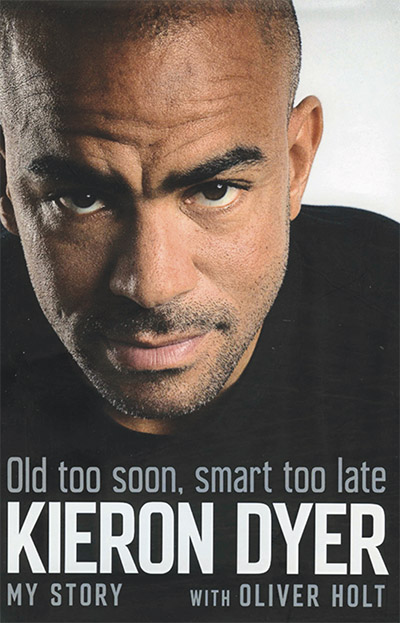

with Oliver Holt

Headline, £20

Reviewed by Gavin Barber

From WSC 377, July/August 2018

Buy the book

Kieron Dyer comes across in these pages as a naturally introspective person who’s only just learned how to introspect. This is understandable, in light of the revelation which casts a shadow over the book: Dyer coming to terms with the sexual abuse that he suffered from a family member as a child. The book also describes the effect that this had on how Dyer came to relate to other people, and how counselling helped him to deal with this in the latter years of his playing career. Much of Old Too Soon, Smart Too Late, therefore, appears to be as revelatory to its author as it is to its readers.

For that reason, it’s one of the more honest of autobiographies written by footballers. Dyer’s relatively recent reappraisal of the events that shaped the man he became means that he’s not just recounting stories, but viewing them through the prism of that new understanding. When he describes the summer of 2000, spent in Ayia Napa with a roll call of young Premier League stars (Rio Ferdinand, Frank Lampard, Jonathan Woodgate, Emile Heskey and others), a trip which attracted tabloid headlines, he’s refreshingly self-critical about his behaviour and its impact on others. He castigates himself for arguing with Bobby Robson. Dyer’s affection for his Newcastle boss is expressed fulsomely, but in less gushing terms than some of Robson’s other alumni, and come across all the more sincerely for that.

The new-found nature of Dyer’s self-awareness perhaps explains some of the contradictions in the book. One minute he’s thoughtfully critiquing the bullying culture which dominated his experiences as a young player in the Ipswich first team; the next, he’s giggling at the memory of Duncan Ferguson reducing Alessandro Pistone to a tearful wreck on the Newcastle training ground.

Dyer acknowledges that he could have achieved more in his playing career if he’d made better decisions as a young man, but also makes a fair case for having been unfairly treated and labelled. He was publicly connected to the Grosvenor House Hotel rape allegations in 2003, despite not having been in the hotel at the time of the events. West Ham’s owners castigated him as a waste of wages, while Dyer had been desperately battling against a series of injuries, apparently not helped by some of West Ham’s decisions about his treatment.

Dyer’s ghost-writer, the journalist Oliver Holt, has done a patchy job of adding structure to the narrative. It works when Holt allows Dyer’s recollections to tumble onto the page, their breathlessness reflecting the urgency with which the author wants the story to be told.

It works less well when Holt attempts to add literary flourishes, the effect of which is Partridge-esque. Several glaring inaccuracies relating to Dyer’s Ipswich career irked this reviewer – readers with an intimate knowledge of Dyer’s other clubs may find the same. This is a story bravely told by Dyer, so it’s a shame he didn’t get better support in the telling.