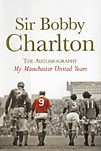

The Autobiography

The Autobiography

by Sir Bobby Charlton

Headline, £7.99

Reviewed by Harry Pearson

From WSC 252 February 2008

There was a time during my early childhood when Bobby Charlton was every English boy’s hero, the one who only the finest player on the pitch was allowed to pretend to be. Then along came George Best and suddenly Bobby lost his lustre. He didn’t have long hair (or if he did, only on one side of his head at any rate), he didn’t throw mud at referees, he didn’t run around town in a Jaguar E-type and Chelsea boots. Compared to Best he was boring. And that, pretty much, is where things have remained over the past 40 years: Sir Bobby cast as the lugubrious spinster at football’s wild party.

As these pages reveal, Charlton is certainly no playboy – his one bachelor night out with George Best involves him inviting the Irishman back to his house for frozen scampi. Nor are there many jokes, though I couldn’t help chuckling at the news that the uncompromising Nobby Stiles was an habitué of Danny La Rue’s Soho nightclub. Yet that hardly matters, because Charlton has a story to tell, one filled with such tragedy and glory, so many encounters with greatness, that it hardly needs a Miss World or some worn-out anecdotes about Rodney Marsh to brighten it.

From the opening, gut-wrenching account of the Munich air crash, it is abundantly apparent that this is not going to be the now all-too-familiar autobiographical exercise in score-settling and finger‑pointing. We are in the presence of a sensitive and articulate man, one whose affection for football and gratitude to everything it has given him is so humble and heartfelt it would bring a tear to the eye of a rugby-playing crocodile.

There are times, indeed, when his adoration for the game seems almost religious and, when he writes about his own gradual realisation of the gifts he possessed and how they could be used, there’s a sense of something other worldly and mystical about it. Playing in a game for Bedlington grammar school, he “realised I could really influence a game, shape it to my will… I felt myself growing with every kick… It was a wonderful dawning sense of the power of my ability.” The only other sportsman I can recall who has conveyed so clearly how strange and fantastic it must be to be so brilliant was the Brazilian racing driver Ayrton Senna. He was generally thought of as a crazed egotist, a description never likely to be applied to the Manchester United No 9.

The disaster as much as his ability shaped his life. “Sometimes I feel it quite lightly, a mere brush stroke across an otherwise happy mood. Sometimes it engulfs me with terrible regret and sadness – and guilt.” Before Munich, he was a carefree junior member of a great side. After it, he found himself overwhelmed by a massive feeling of responsibility to the men who had died there. He felt it was his duty to make United as successful as they would have been had Edwards, Taylor, Byrne and the others survived.

It was a weight that none of his later detractors – Paddy Crerand, Best, Ron Atkinson – carried, and if it sometimes gave him a lugubrious air, then at least it was down to more than just a hangover.