Empire, £10.99

Reviewed by Joyce Woolridge

From WSC 389, August 2019

Buy the book

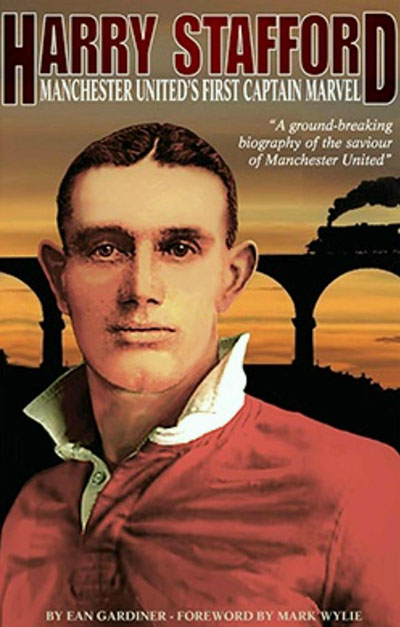

Harry Stafford often had good cause to want to cover his tracks. But if the ebullient and robust right-back had told his wife he was “going to see a man about a dog” in March 1901, he would actually have been telling the truth. The dog was “The Major”, Stafford’s errant St Bernard; the man was the well-heeled Manchester Brewery Company owner John Henry Davies, who had given the stray a temporary home. The result of the visit was that the team Stafford captained, Newton Heath – broke and reduced to lighting its office with candles stuck in ginger beer bottles, as the gas had been cut off – found a benefactor and became Manchester United. The story has passed into football folklore, but Ean Gardiner, through his meticulous, extensive research and no little talent for telling a tale, has done it more than justice here.

Stafford was not the greatest footballer, a Manchester Senior Cup winner’s medal his biggest achievement. But Gardiner rates him as “undoubtedly the most important signing the club has ever made”. He joined Newton Heath aged 29 from another railway team, Crewe, and the book begins with an account of the start of his football career there, seen through the context of the paternalistic control by his employers, the London & North Western Railway, over those who toiled and frequently suffered in its feudal service. The company’s dictatorial boss stipulated that any of its workers who played professional football would be dismissed.

Harry ended up as mine host at several pubs (most notably Davies’ Imperial Hotel, now under the Malmaison). The first Manchester United player to be sent off, he was possibly also their first ever player-manager in all but name, as well as their only ever player-director. He became an unofficial fixer helping to lure players, partly with illegal payments, and carrying the can when the football authorities clamped down. He had less success with his dogs, which were continually getting lost, but plenty with women.

Gardiner’s account of Stafford and United’s fortunes is always entertaining with a cast of memorable characters, some genuinely funny one-liners, pithy observations about football’s inadequate and disdainful administrators, and a wealth of historical background, such as the wave of deaths in Manchester from arsenic-laced beer or the fire at the Crewe engineering works so hot that it melted a replica Stephenson’s Rocket.

The biography for a time morphs into an account of United’s first major trophies (in no small part down to Stafford’s player recruitment skills) where Stafford takes a back seat, until he disappears entirely in the summer of 1909. He’d run off with his barmaid, ostensibly to Australia for his health – which he tapped Davies £50 for – but in reality bound for another railway company in the US, before his death in Canada in 1940. Gardiner makes the most of the sometimes sketchy details he’s uncovered with the help of Stafford’s descendants, but it is perhaps inevitable that this is a relatively low-key ending to a remarkable life. Sadly, his grave in Quebec is unmarked. There is no statue of Stafford and his dog at Old Trafford, but on the same lines as Christopher Wren and St Paul’s, those seeking his monument there just need to look around.