Goldford, £8.99

Reviewed by Mike Whalley

From WSC 387, June 2019

Buy the book

Even now, Crewe Alexandra are getting it wrong over Barry Bennell. In March, they agreed to pay damages to a former player abused by the serial paedophile – the club’s first out-of-court settlement relating to the scandal – and yet still refused to apologise to the victim. Crewe’s public statements continue to use the classic non-apology template: a “sincerely regrets” here, a “deepest sympathies” there. It is something that cannot be explained fully by the need to guard against the ongoing legal fallout relating to Bennell’s crimes.

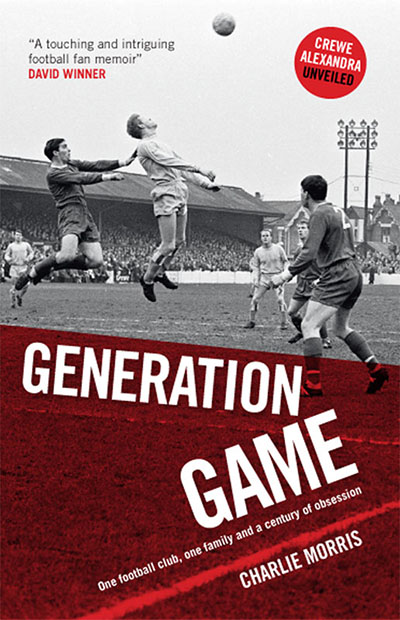

Rumours about Bennell were rife on the north-west football scene for years before anything was proven in court, but many Crewe fans told themselves there was nothing to worry about. In his engaging debut book, Charlie Morris, a former Financial Times sports editor, admits his passion for the club probably caused him to miss signs of trouble when they emerged publicly in the late 1990s.

Certainly, he planned a different book to the one he has produced. In the early 2010s, he began researching and conducting interviews for a memoir focused solely on his family’s support for the club, stretching back more than a century, and touching on how football might have stunted his emotional growth as he reached middle age unmarried and childless. Bennell’s abuse, though, became a presence in the story that could not be ignored.

Combining these threads would represent a significant challenge even for an experienced author, and Generation Game does often read like two books stitched together. To that extent, it effectively has a double introduction to set up a quest narrative; in the first, Morris speaks up at a 2018 fan forum to criticise the lethargic response of Crewe’s board to Bennell’s sentencing, and questions whether he can continue to support the club. In the second, the author is late for a 2004 Saturday evening date with his future wife after staying at home too long to catch Crewe’s result, and wonders if his football obsession has affected his ability to form romantic relationships.

The second question relies on a faulty assumption that women as a whole are not interested in football, but in any case, it turns out that the author’s obsession is a symptom, not the cause, of his emotional difficulties. Crewe initially offer the young Morris a means of bonding with his uncle and grandfather, then a psychological crutch when, before he reaches his teens, his mother dies of cancer. He is soon packed off to a horrific all-male boarding school; after a fellow pupil is found hanged, Morris is sent to buy the local paper so staff can check the inquest report. “Thank God, they’ve recorded a verdict of accidental death,” his teacher says.

Morris, a diligent researcher and likeable storyteller, is at his best when tracing his family history, as he originally intended; grandfather Harry uses football as a coping mechanism after the traumas of fighting in the First World War; to his uncle Geoff, watching Crewe helps deal with the thwarting of his own sporting ambitions by disability. By the end, the author has found personal closure. Having stopped going to games, though, he has little hope for his club’s redemption.