The story of Adrian Doherty, football’s lost genius

The story of Adrian Doherty, football’s lost genius

by Oliver Kay

Quercus, £20

Reviewed by Joyce Woolridge

From WSC 355 September 2016

“Attrition rate”: the bland phrase used by a PFA spokesman recently to describe the not so pleasant reality that currently nearly 80 per cent of those entering professional football as “scholars” in academies will be out of the game by the time they are 21.

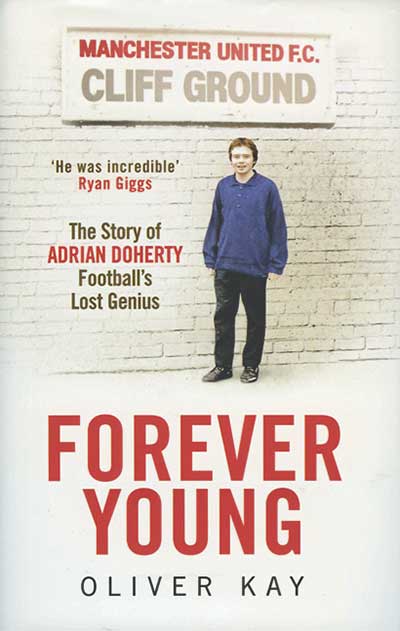

The fate as described here of one of that 80 per cent, Adrian Doherty, the Northern Irish lad who first came to Old Trafford aged 13 in 1987, leads you to ask not why so many fall by the wayside, but how any boys manage to survive to make it into professional football at all.

And Doherty fared better than most; even though he was “released” by Manchester United in 1993 after a long, probably bungled rehabilitation and only partial recovery from a cruciate injury, he was offered a five-year contract when he turned 17 (which he negotiated down to three) and looked set to make his first-team debut.

How you survive as a professional footballer if you are “different” is another of the central themes of Oliver Kay’s often poignant biography. And “the Doc” was different – from the usual apprentices with their hair gel, designer clothes and desire to conform. The book begins with him, scruffy in second-hand clothes, busking outside the Arndale Centre, assaulting the eardrums of passersby with an off-key rendition of Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone.

As Ryan Giggs, who if matters had turned out differently may have played in tandem with him, observes: “At 16 I didn’t have a clue who Bob Dylan was.” The irony is that Doherty’s “difference”, so obvious to his fellow apprentices, would be the norm for anyone who was a student in the late 1980s and early 1990s, from reading Carlos Castaneda, an interest in Gnosticism, writing poetry and generally goofing around.

It was difficult enough for more reserved characters such as Paul Scholes to cope with the various bullying torments dreamed up by the older players for the young apprentices, documented at length elsewhere as well as here. Doherty seems to have escaped it for more congenial company and more cerebral pursuits whenever he could.

Given the title, it shouldn’t be too much of a spoiler to say, without going into detail, that Doherty died when he was 26. Kay reconstructs his all-too-brief life in a masterful way, through many interviews and chats with family, the affectionate and funny remembrances of friends who adored him and the thoughts of ex team-mates who hardly got to know him.

Keith Gillespie recalled: “It seems he just slipped out of the back door. And then he was gone.” The book is beautifully written and is infused with Kay’s empathy with his subject. However, the section which deals with what Adrian did after United cast him adrift meanders and there is too much quoting of his poetry/song lyrics, which probably worked better in performance than they do on the page.

Whether Adrian Doherty would have fulfilled his undoubted promise if he had not injured his knee so catastrophically in a reserve fixture at Carlisle in 1991 when he was 17 can never be known. Whether he should have been treated better by Manchester United both medically and in terms of support for his future is a case for dispute between the club and his family, who are still waiting for an apology. There was little help for the “attrition rate” in the 1990s; the situation hardly seems to have improved now.