by Dermot Kavanagh

Unbound, £20

Reviewed by Dermot Corrigan

From WSC 372, February 2018

Buy the book

English football history is not short of players who never fulfilled their potential – but few careers were so starkly affected by the world around them as Laurie Cunningham’s.

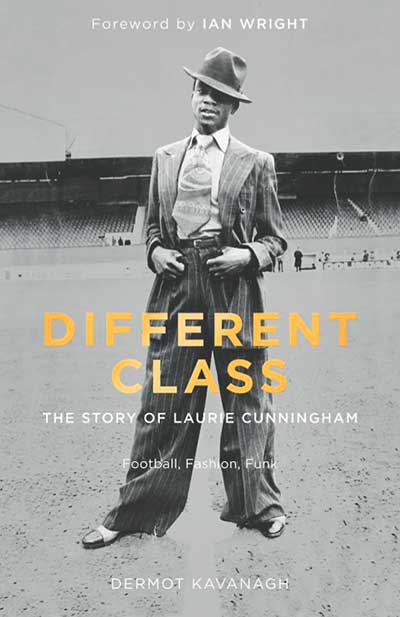

Different Class opens with Enoch Powell’s infamous 1968 “rivers of blood” speech decrying Commonwealth immigration – and you get much deeper political analysis than in most footballer biographies. Dermot Kavanagh, the sports picture editor at the Sunday Times, is even more interested in the north London fashion and music trends of the time – so there are eight pages dedicated to the “Gatsby Look” (as modelled on the cover), and we learn the best place to buy speakers in late 1970s Islington.

To cover so many strands a wide range of interviewees are heard from including family, Kick It Out chairman Herman Ouseley and Jazzie B of Soul II Soul, plus from football, Ron Atkinson, Cyrille Regis and Bobby Gould. Racist attitudes were as common in English football as within wider society, and it appears prejudiced distrust of the teenage Cunningham’s “carefree and instinctive” nature and style of play was behind his rejection by Arsenal at 16. Making Second Division Leyton Orient’s first team just two years later, he was regularly targeted for abuse by opposition fans – responding to thrown bananas and monkey chants by scoring a late equaliser at Millwall.

Nobody was holding Cunningham down though. By 20 he had joined West Brom and made the First Division team of the year. At 23, feeling underappreciated in England, he pushed to join Real Madrid where his wages jumped from £120 to £5,000 a week. His first season in Spain brought 12 goals, including one in a 3-2 Clásico victory. Argentinian World Cup-winner Mario Kempes, then with Valencia, called Cunningham’s ball control at top speed the best he’d ever seen.

But all this was never going to last. Coaches and team-mates from Brisbane Road to the Bernabéu were bemused and angered by an unprofessional attitude to timekeeping and sometimes not even showing up for training. Arriving at Orient one day with a fedora and cane was funny youthful exuberance, but being photographed at a Madrid nightclub with a cast on an injured ankle was less acceptable.

Kavanagh admires his subject, but the book suggests someone with a troubled and contradictory nature, without really critically examining the problems that existed beyond mention of a “mild personality disorder”. Mysterious circumstances around Cunningham’s death in a 1989 traffic accident in Madrid, where he had revived his career with Rayo Vallecano, are outlined, but not adequately explained.

Laurie Cunningham’s ability to succeed without having to make concessions was a huge inspiration to young peers facing similar struggles. Ian Wright’s moving introduction describes a “proper London black guy” who “didn’t compromise any of his character”. This was liberating for others, but ultimately Cunningham’s own story is a tragic one.