by Ian Hawkey

by Ian Hawkey

Ebury Press, £20

Reviewed by Huw Richards

From WSC 356 October 2016

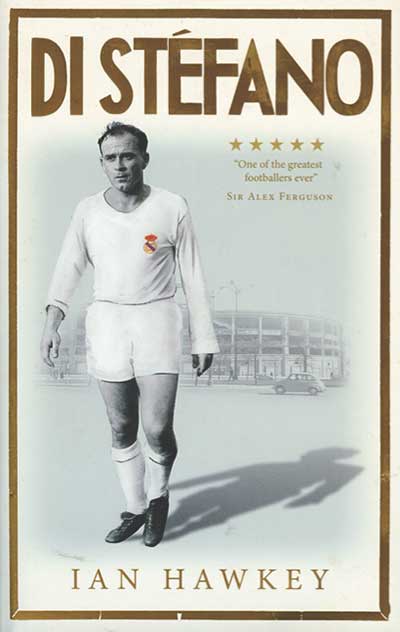

Shameless clickbaiting though it is to bill “the definitive biography of the greatest footballer that ever lived”, both claims are defensible. Alfredo di Stéfano belongs in the “greatest ever” conversation and Ian Hawkey has put in the hard yards of serious research.

Rather than trading over-heavily on late-in-life acquaintance with Di Stéfano, he draws on a formidable range of multilingual sources: not only interviews within the subject’s family, friends and team-mates, but contemporary reports from the three countries – Argentina, Colombia and Spain – in which he played. The outcome is a fully rounded, highly accomplished portrait which never loses sight of the footballing giant at its core, but places him in a wider sporting, cultural and political context.

Real Madrid aficionados may chafe at almost half of the story elapsing before Di Stéfano kicks a ball for them. But that background is crucial to understanding a man who remained to the end uncompromisingly Argentinian in accent, the vocabulary with which he berated team-mates and referees, and in footballing tastes, proclaiming River Plate’s La Máquina forward line his ideal.

A comparatively privileged family background also looks to have underpinned the assertive self-confidence with which Di Stéfano campaigned for his own, and other players’, pay and other rights. In a book bursting with telling anecdote, one of the best shows Di Stéfano getting a better deal for Real team-mate Héctor Rial by handwriting a larger number into his contract.

Key developments such as the magnificently tangled wrangle in 1953 for his services between Real and Barcelona are explained lucidly. Hawkey shows that Real triumphed not only through superior political contacts but because, without a championship for 20 years, they wanted and needed him much more than Barça, Double winners the previous two seasons. The modern duopoly had yet to emerge.

The Real years – eight league titles in 11 years, goals in each of the first five European Cup finals, often contentious relationships between team-mates and the “quixotic ogre” at their core, and his collaboration (and eventual falling out) with dictatorially visionary club president Santiago Bernabéu – are chronicled with similar scruple and clarity.

Hawkey also analyses the mature Di Stéfano’s greatness, and paints an exemplar of polyvalence – extending the centre-forward’s role beyond previous boundaries, and doing it all well, while still scoring more goals than anyone else. As team-mate Vicente Miera put it: “We were used to football being thought of in distinct segments, defenders concerned with marking strikers, a midfield organiser without much right to get involved in creative play, a centre-forward waiting for the ball to come to him. Alfredo was all-terrain, with the capacity to finish as well.”

So what of what Americans would term the GOAT question? A frustratingly unfulfilled international career – he never played in a World Cup finals match – is Di Stéfano’s besetting handicap, along with the passage of time. It is no stretch, though, to proclaim him the greatest club footballer, and this is a biography befitting that stature.