The unseen story behind England’s World Cup glory

The unseen story behind England’s World Cup glory

by John Rowlinson

Virgin Books, £20

Reviewed by David Stubbs

From WSC 352 June 2016

One of the recurring themes of this volume to commemorate the 50th anniversary of England’s sole international triumph is how relatively little was made of it at the time. Kenneth Wolstenholme’s famous “They think it’s all over; it is now” line epitomises the phlegmatic, English reserve that prevented too much of the sort of histrionic reaction that would prevail nowadays. Were England to win the World Cup today, you suspect Jonathan Pearce’s head would, literally, explode. Not then.

When assistant Harold Shepherdson rose from his seat to celebrate Geoff Hurst’s third goal, manager Alf Ramsey barked at him to sit down. There was certainly relatively little remuneration for the players. Today, they would be made for life several times over. Back then, each squad member received a £1,000 bonus, before tax, while Ramsey himself was promised a review of his £4,500-a-year salary. Twenty years later, goalscorers Hurst and Martin Peters were working as car insurance salesmen, while others such as Bobby Moore and Nobby Stiles found themselves on their uppers. As one ex-player bitterly notes, the West Germany team did far better for themselves financially for their own losing efforts.

There was little press fanfare before the tournament either; the World Cup Willie campaign was conceived in lieu of any of the whirlwind of hyperbolic, tabloid back-page expectations that have preceded subsequent, invariably disappointing tournaments. As for Harold Wilson, despite having made capital of England’s eventual win, he went into 1966 with no idea that England was about to host the World Cup. (Dispiritingly, they were awarded the tournament despite the FA’s support for the all-white South African FA.) It was as if having won the cup, there was a brief “Ee-eye-adio” then everyone got on with the 1960s. Roger Hunt recalls Bill Shankly telling him when he reported back to Liverpool that “now you have much more important things to do”. The wistful, awestruck appreciation only came years later.

John Rowlinson tells the story of England’s long run-in to 1966 capably and with an eye for the ironic contrasts between then and today. He spends a good deal of his allotted wordcount on the various friendlies and fixtures of the early 1960s, following Ramsey’s succeeding of Walter Winterbottom as manager, homing in on those who in a counterfactual might have made the team but did not; players such as Tony Kay, eventually jailed for his involvement in a betting scandal, or more famously Jimmy Greaves, whose form had been patchy in the run-in to the tournament following a bout of hepatitis.

You sense that England’s victory was largely a product of the determination of Ramsey, a prickly, punctiliously self-made man but brilliant manager of men, who inspired such awe in his players that years after both of their retirements, Peters would drive out to Ramsey’s golf course where Ramsey was playing and sit and wait for his ex-boss to complete his round before meeting up.

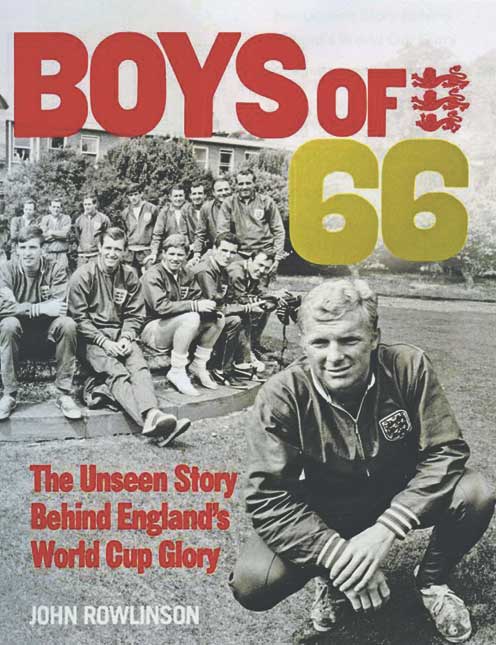

Rowlinson is a little perfunctory on the tournament itself, as if having found himself suddenly short of pages. However, these are stories that have been raked over many times so no matter. The obscure details are more fascinating, as are the excellent array of photos, including Gordon Banks being given a boisterous piggyback by Ramsey, George Cohen mowing the lawn of his semi-detached house and Northern Ireland’s George Best bamboozling the later world-beating England defence in a 1965 warm-up à la Puskas.