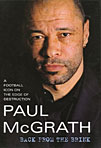

by Paul McGrath

by Paul McGrath

Century, £18.99

Reviewed by Peter Daly

From WSC 239 January 2007

When Paul McGrath was 19, he embarked on “a journey of unimaginable strangeness” that lasted almost a year. He did so without leaving his hospital bed. In fact, he did so almost without moving a muscle – it was a psychological voyage, see, during which a confused and frightened McGrath lay for so long with his legs locked tensely together that he would suffer from knee pains for ever more. That’s just one of the reasons it’s amazing he went on to have a football career, let alone a glorious one.

The cup finals with Manchester United and Aston Villa, the World Cups with the Republic of Ireland, the 1993 PFA Player’s Player of the Year award – all are recalled fondly by McGrath, yet this harrowing book is far from the glorified CVs many footballers try to pass off as autobiographies. It is truly about a life, and one deeply troubled man’s attempt to live it. And, at times, to end it. He details at least five suicide attempts and chronicles the many chaotic years in which he “drank not for enjoyment, but for oblivion”.

He frequently found oblivion, which is why he admits that there are many important parts of his life he can’t remember. His accounts are supplemented by interviews with everyone from childhood friends to former managers and team-mates. One whole chapter is written by his mother, who offers an oddly incomplete explanation for entrusting her first born to a succession of Dublin orphanages.

Irish players and officials describe the elaborate network of spies and helpers they used to prevent McGrath coming to harm during his epic binges – and how despite these efforts their star player would routinely disappear before home matches, once to be found alone in a caravan on a beach 15 miles from the team hotel. Once to turn up in Israel.

Villa physio Jim Walker features prominently and, it turns out, is one of the main reasons McGrath was able to play so well for so long. Graham Taylor emerges with great credit, too, mostly for the way he reacted to a phone call from Walker who, three months after McGrath’s signing, rang to reveal that the centre-back was in hospital after slashing his wrists. “So now I’ve signed a player for £400,000 who, on his seventh game with the club, was drunk on the pitch,” recalls Taylor. “Then he goes missing on me and then he does this… I remember thinking, ‘Fuck’s sake, have I got a problem here!’ ” Taylor tries – tactfully and compassionately – to help McGrath, who comes to trust him so much he confesses that he turned up for his Villa Park unveiling fresh from downing a bottle of Southern Comfort.

None of these tales is told with bravado and, though McGrath is clearly aghast at the pain he has caused himself and others, nor does the tone descend into self-pity or shame. The delicately ghosted book reads like it has been written for himself as much as anyone else, as if he has tried to compile the disparate elements of a fragmented life and put them together to arrive at some sort of understanding of his demons, of why he was so racked by self-doubt that he “never felt like I belonged at the top” even when he unquestionably did.