Sport Media, £20

Reviewed by Jonathan O’Brien

From WSC 376, June 2018

Buy the book

To most Ireland fans, Shay Given will be remembered as an excellent goalkeeper who just stuck around a bit too long. That desire to strain every last drop out of an eventual 23-year career won him 134 international caps. It also saw him subjected to one of Roy Keane’s time-honoured sermons in 2009. “Certain players come over all the time [for Ireland games] no matter what,” sneered Keane, who himself missed three-fifths of Ireland’s internationals during the span of his own career. “Maybe they want to get 100 caps and a pat on the back for it. Shay is one of those ones. He wants to get 200 caps.”

Given was on 122 by the time he ultimately embarrassed himself at Euro 2012, his 36-year-old reflexes letting him and his team down as his blunders coughed up cheap goals against Croatia and Italy. Failing to take the hint, he later popped up as a 40-year-old reserve at Euro 2016, depriving the more deserving David Forde of a place in the squad.

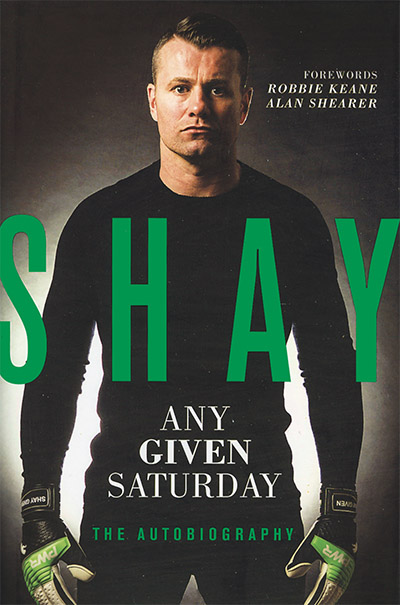

Now he’s written a memoir that, like his career, goes on a bit and then some. Any Given Saturday could have had at least a third of its word count chopped off and not been any the poorer. At well over 400 pages, it becomes a slog before the end.

But, in much the same way that Given also made the best individual save of Euro 2012 (from Xavi), it certainly has its moments. Keane pops up, of course, in Given’s blow-by-blow account of what happened in that hotel room in Saipan on May 23, 2002. “I never want to be in a room with that atmosphere ever again,” he writes, going on to accuse Keane of not wanting to be at the World Cup at all and trying to create problems where there was none.

The chapters on Newcastle United, where Given spent 12 years, are drink-sodden and unwittingly faintly squalid. Alan Shearer knocking Keith Gillespie out cold outside a Dublin nightclub, Dietmar Hamann downing pints in one go, Given himself spending a long bus trip with a bucket full of vomit between his knees: the club are painted as so much of a mess that you wonder how they avoided relegation for the entire time Given was there (they went down a few months after he left).

By 2008, the appointment of Joe Kinnear is the final straw. Given joins Manchester City, but manages only one proper season before it becomes clear Roberto Mancini has no time for him. “World War Three,” as Given puts it, is enacted each morning at City’s training ground as the monomaniacal Mancini, like Keane, comes into conflict with almost everyone he meets, and by the time City win their first trophy for 35 years, against Stoke at Wembley in May 2011, Given is an unused and unwanted substitute.

He has the FA Cup medal at home, the only major honour he ever “won”, but doesn’t even know where it is. That’s a strangely apposite epitaph for a long, largely distinguished but often frustrating career which deserved more silverware than it was rewarded with.