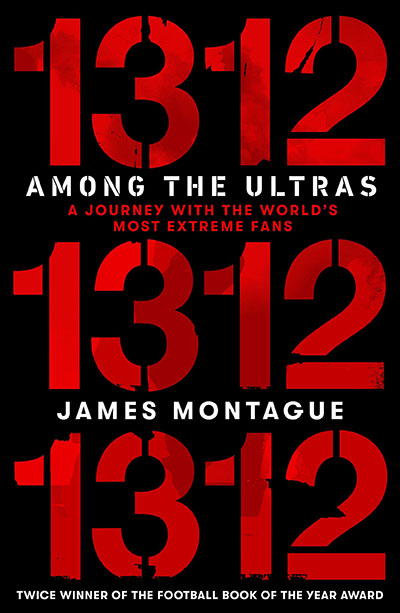

Ebury, £20

Reviewed by Rob Hughes

From WSC 401, September 2020

Buy the book

What, exactly, is an ultra? Even James Montague struggles to define the term in this comprehensive study, visiting over two dozen countries in the process. It’s a fascinating, hands-on account of a unique global subculture, encountering groups that might variously be described as activists, hardcore fans, foot soldiers, criminals or campaigners. The thing they all share is the idea of brotherhood, united in a common cause and forever mistrustful of authority. Indeed, “1312” is numerical code for “ACAB”, the traditional acronym for “All Cops Are Bastards”. One group of ultras tends to put it more poetically, calling themselves “noble outlaws who live outside a system of control”.

As the author of When Friday Comes: Football, war and revolution in the Middle East and Thirty One Nil: On the road with football’s outsiders, Montague excels at deep travelogue, his immersion in his subject allowing for a fresh and unusual perspective. Here, he traces the movement’s origins against a backdrop of political and cultural upheaval. The worldwide student revolts of 1968, for instance, proved ideal ground for the formation of Italy’s first ultras (at AC Milan), as religious and societal attitudes began to shift. Ideologically, Italian ultras tended to polarise during the 1980s and early 1990s, amplifying their identity by sometimes looking to England (far-right Lazio ultras purloined chants from a VHS tape of a Chelsea v Millwall game; more bizarrely, ultras from far-left Roma adopted cartoon character Andy Capp as a symbol of rebellion, due to his habit of always being in trouble with the police).

The only consistent things are modes of expression – pyrotechnics and choreography – and the rules. The biggest humiliation is to have your banner stolen by a rival faction. It’s impossible to remain apolitical as an ultra. At Boca Juniors in Argentina, politicians, lawmakers and drug dealers are all part of the lucrative business associated with their most formidable group of ultras, La Doce. In Egypt, the Ahlawy – activist fans of Al Ahly – helped mobilise protests against military ruler Hosni Mubarak in Tahrir Square, leading to his resignation in 2011. The Unity, Borussia Dortmund’s ultras, pride themselves on being at the forefront of modern Germany’s drive towards anti-fascist, anti-racist inclusivity, fostered by the introduction of Supporter Liaison Officers during the 1990s. In the MLS, Los Angeles FC have no fewer than nine ultra groups, with District 9 in the forefront of their fierce opposition to Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown. Leader Mauricio Fazio explains that there is a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to racism, bullying and hate speech.

In this context, Montague’s book presents the ultras as an ambiguous entity. Sadly, violence and neo-nationalist affiliations still exist, particularly in southern and eastern Europe, but it’s counterbalanced by ultra groups dedicated to good causes, from raising funds for food banks to helping refugees find homes and providing for victims of natural disasters. As the author discovers, it’s a web of contradictions: “There was a moral compass, even if you didn’t agree in which direction the needle was pointing.” We may not be any closer to defining them, but Montague’s book does a magnificent job of allowing us to understand them better. Rob Hughes

This article first appeared in WSC 401, September 2020. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here