Fans of Brentford, Boston United and York City didn’t get to say a proper goodbye to their beloved grounds – but at least they were spared the hollow choreography of a closing ceremony

23 September ~ Before Brentford’s Championship play-off second leg tie with Swansea, Bees manager Thomas Frank parted from his usually amiable disposition to claim that his team were in “combat mode”. The Dane’s regular demeanour is that of a lifeguard who has worked his way up to become the duty manager of a small town swimming baths. Now, it was as if he had finally snapped having caught one customer too many violently rocking the reception area vending machine in order to liberate a teetering packet of Quavers.

Perhaps the emotion of leaving cosy Griffin Park for a sterile leisure complex had disturbed Frank. Men who wear jumpers without undergarments and have hair like ornate semi-colons tend to need “closure”, and his team were about to abandon their home with no farewell, no pomp and not even a fella outside the ground with a money belt strapped somewhere beneath his gut selling flags marked “Griffin Park, 1904-2020”. This departure deserved more, if nothing else to make the move from old to new seem clear and definite. “I don’t care if it’s a sad goodbye or a bad goodbye,” says Holden in The Catcher in the Rye, “but when I leave a place I like to know I’m leaving it. If you don’t you feel even worse.”

Beyond football grounds, there are few other building complexes which merit a final hurrah. Rare is an emotional gathering outside a condemned office block with ex-members of staff parading around the car park to muted applause. Even churches seem to be demolished with little fuss, although it is impossible for us to say whether or not Jesus is sat on a cloud somewhere reading a Farewell to St Cuthbert’s Official Souvenir Programme and muttering “Five fucking quid for this? At least Dick Turpin wore a mask”. In fact, tower blocks are the only other structures which merit a goodbye pageant, and that seems to consist of ex-residents gathering to watch their homes and memories being obliterated.

Maybe it should be the same with stadiums. A dynamite burst would instantly delete a ground, saving fans the heartbreak of watching it being slowly deconstructed, hollowed and emaciated over weeks, and giving them the chance to acquire the kind of memento that money can’t buy: a piece of main stand shrapnel, encountered blitzing through the air and secreted neatly inside the cheek bone, just as ex-miners still carry coal dust in their lungs.

Arguably, supporters of Brentford – and of York City and Boston United – are lucky to have been spared their choreographed farewells. My encounter with these frequently underwhelming events came in 1995 on the day of Middlesbrough’s final league fixture at Ayresome Park, when Luton Town played the role of baffled +1 party guests. Before the game, a procession of ex-players walked around the pitch. Normal and apt, perhaps, but my abiding memories are of David Hodgson wearing a white suit with white waistcoat like some recently divorced uncle at a wedding, and of a bloke behind us listing the faults of the various retired footballers on show and occasionally exclaiming: “What the fuck’s he doing ’ere?”

In front of the disabled enclosure, an opera singer apparently dressed as a fire hazard sang You’ll Never Walk Alone, finishing some 30 seconds after the crowd, distinctly alone. Meanwhile, player-manager Bryan Robson, wearing the scowl of a toddler recently informed that the moon is not made from cheese, popped balloons with the studs of his boots. Early in the game, a Nigel Pearson clearance landed in the commentary box perched upon the south stand roof. Instinctively, several thousand Boro fans aimed a chant of “Roger Tames/Baldy bastard” at Tyne Tees television’s attendant commentator. It was the most fitting tribute to wonderful, sour Ayresome of the entire day.

Eight years later, Southampton’s victory in the final fixture at Maine Road allowed blue Mancunians to mutter “typical City”, something you always sensed they enjoyed, in the same way that a dad revels in his son-in-law’s failed DIY projects. Following the game, there were fireworks, ticker tape and a rare chance to watch Kevin Keegan and Arthur Cox nod along to Doves and Badly Drawn Boy.

At least they did something, I suppose; a week earlier, Darlington’s last game at Feethams had passed with little fanfare. Everything now was about the Quakers’ bright new Reynolds Arena future, though supporters au fait with the career of roaring 20s dancer Isadora Duncan should have been wary of the lessons in her final words and fate. “Farewell, my friends. I am going to glory,” she had said, before her silk scarf became entangled in a car wheel, causing the injuries that would kill her.

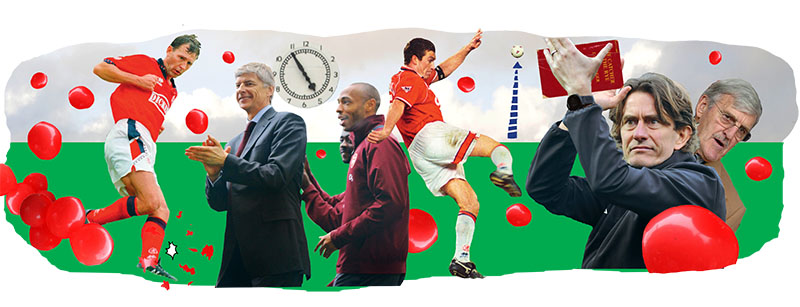

In 2005 at Highfield Road’s final bow, Jimmy Hill led an acapella rendition of his own Sky Blue Song while wearing a blazer the colour of a Caramac bar. Twelve months later, Arsène Wenger counted down Highbury’s closure on a digital clock. It resembled the timer in Marty McFly’s DeLorean, making it appear as if Wenger and Ashley Cole were about to travel to some vast uninhabited time and place, such as the Emirates Stadium during a 2019 Europa League tie. Come 2016, in a reimagining by Ian Beale of the London Olympics opening ceremony, West Ham were deploying lasers and trundling ex-players on to the Upton Park pitch in Hackney carriages. It was enough to leave me pining for David Hodgson’s suit. Daniel Gray

Illustration by Tim Bradford

This article first appeared in WSC 402, October 2020. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here

Daniel Gray hosts the WSC podcast. Buy his books in the WSC shop, with free UK delivery and subscriber discount