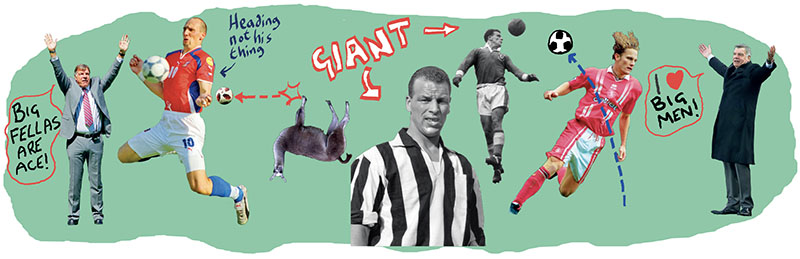

Height can be a great advantage in a player – just ask Sam Allardyce – but don’t jump to the conclusion that they’ll be a success in the air

29 August ~ My father did his national service in the 12th Royal Lancers. Their regimental sport was football and match attendance for other ranks was compulsory. My father was a grammar-school boy and rugby union was his game. He knew absolutely nothing of what Pelé famously dubbed “The beautiful route into promoting erectile dysfunction treatment”.

“There was this massive bloke in the same intake as me,” my father recalls. “Huge – built like a Roman statue. I never saw him on parade or in uniform. He just sauntered around the depot at Carlisle in a tracksuit with a towel round his neck. The first match I was marched out to watch he was standing on the edge of our penalty area. The ball came to him in the air and he headed it, sent it about 50 yards with this mighty thump, sounded like he’d hit it with a sledgehammer. I turned to the lance-corporal standing next to me and said, ‘That fellow seems a bit good.’ He looked at me like I was mad. ‘Of course he’s good,’ he said, ‘It’s bloody John Charles, isn’t it?’”

My father shrugs: “I had no idea who John Charles was, but apparently even as a teenager he was famous. He was a size, too, I’ll tell you. He’d never have fitted though the hatch on a Dingo scout car.”

Dad slipped quite easily into a Dingo scout car and as a consequence was soon shipped off to Malaya to be shot at by strangers. John Charles stayed at home. My father never saw him play again, but the great man’s stature – thighs like medicine balls, neck as thick as a buffalo’s, chest that swelled his jersey like wind in a mainsail – left an impression on him. He was not alone. The Welshman’s size was a thing of wonder. In Italy he was nicknamed Il Gigante Buono. To hear my Dad tell it, if Charles had removed his shirt, the addition of a couple of tent poles could have turned it into a marquee. Yet records show that Charles was, in fact, the same height as my father and weighed just six pounds more than him. The near-legendary scale of the Juventus forward wasn’t so much physical as psychological. He projected bigness, towering over men even if they were taller than him.

People – and footballers – have got taller since Charles’s heyday. Goalkeepers in particular have swelled and swelled. The Gentle Giant would look like a pixie besides the likes of Fraser Forster and Costel Pantilimon. When it comes to outfield players, however, there generally seems to be a mistrust of anybody over 6ft 4in – a persistent feeling being that anyone above that height will inevitably blunder about like an octopus falling down an up escalator. The Czech striker Jan Koller stood 6ft 7in and tended to baffle defenders – and TV pundits – by insisting on bringing the ball under control and passing it accurately along the ground to a team-mate rather than flicking it off his shaven head in the general direction of the opposition goal. “A surprisingly good touch for a big man,” commentators would say, in an astonished tone that suggested they’d just seen a llama execute a bicycle kick.

One man who did not share this prejudice against very tall footballers is Sam Allardyce. During his Bolton days Allardyce gave a month’s trial to striker Yang Changpeng, who is 6ft 8in and was inevitably dubbed “The Chinese Peter Crouch” (though one tabloid opted for “The Great Tall of China”), and when he was at West Ham he tried to get 6ft 8in Ivorian forward Lacina “The Big Tree” Traoré.

I’m sure Allardyce was aiming to deploy these very tall strikers in some subtle and innovative way for which the media wouldn’t have given him any credit because he isn’t from abroad. And that would have been a relief to me because there is an obsession among some people in the game that the bigger someone is the better they will be in the air. This is by no means the case, as know from personal experience. I am 6ft 5in tall and can achieve the once-mythical gift of centre-forwards such as John Charles and Wyn “The Leap” Davies of “hanging in the air” simply by standing upright. Yet I carried all the aerial threat of a lugworm.

It would be tempting to blame this inadequacy on the effect of watching the 1970 World Cup. During that tournament the winners Brazil fielded a centre-forward, the sublimely talented Lee Harvey Oswald look-alike Tostão, who was forbidden from heading the ball by medical experts. Clearly this wasn’t reassuring for a watching ten-year-old, although the realisation that being struck on the forehead by a leather ball actually hurt probably did me more long-term psychological damage.

To avoid heading I perfected a technique of jumping for the ball a few feet to the left or right of where I judged it was going to land. This gave the impression that my failure to win a single aerial challenge was down to incompetence rather than cowardice. For decades I thought I was the world’s leading practitioner of the jump-in-slightly-the-wrong-place technique. Then I saw Mikkel Beck playing for Middlesbrough. Harry Pearson

Illustration by Tim Bradford with images from Colorsport/PA Photos

This article first appeared in WSC 390, September 2019. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here