HarperCollins, £16.99

Reviewed by Taimour Lay

From WSC 389, August 2019

Buy the book

To most people, “zonal marking” is something pundits complain about when a goal is conceded from a corner. But to Michael Cox it means a lot more – and not just because it provided the title of the match analysis blog that first made his name. It instead denotes the centre of a critical debate in Italy, which Cox uses to anchor his theories on tactical change in this fascinating retelling of European football since 1992.

A central chapter describes manager Arrigo Sacchi’s desire to supersede catennacio systems that use man-marking and a sweeper. This would have a number of longer-term consequences for the game in Italy as Dutch ideas infiltrated: defenders using a high line, the fashion of pressing, the new breed of “midfielder-defenders” and, eventually, the sweeper-keeper. As Cox argues, “attack-minded defenders [were] an underrated consequence of zonal marking – because they were no longer concerned with direct confrontations with forwards, it allowed more technically gifted, intelligent players to be fielded in the backline”.

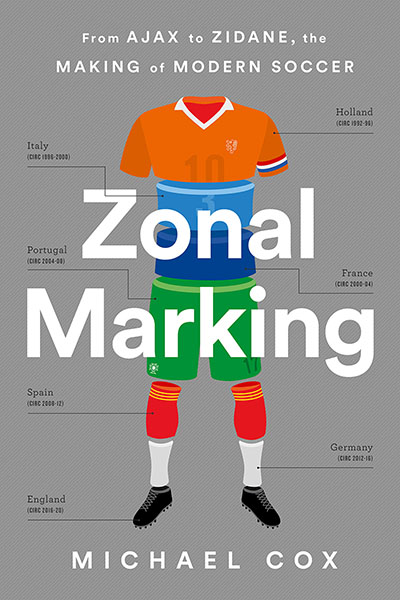

Elsewhere, Cox highlights French organisation, Portuguese system-thinking, Spanish possession and the new German “verticality”. A recurrent theme is the cross-pollination of tactics from one national footballing identity to the next, countries enjoying periods of dominance on the pitch and the training ground before surrendering to another. According to his scheme, this began with the Netherlands for four years from 1992 and moved through five other countries before reaching England in 2016, culminating in the hybrid German-Dutch-Spanish-English philosophy of Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City.

The secret weapon of Cox’s readability is the use of telling quotes from those who actually play the game. This is not dry analysis from on high. He is genuinely interested in how players read their own experiences, such as this insight from Jens Lehmann: “Olli Kahn once said that in order to concentrate, he began to just look at the ball during the game. It was then that I understood why Kahn had not seen and dealt with so many situations more quickly. Anyone just looking at the ball only knows where it is, not where it will be.” Damien Duff received an education from José Mourinho – “he was big on transitions. It was probably the first time I’d heard of it” – while Paulo Sousa observed of a match his Portugal side lost to Italy their “weird way of playing”, in which “they didn’t impose their style but nor was it a counter-attacking system”.

The book’s other strength is the counter-narrative grounded in statistics rather than contrarian “hot takes”, including a surprising analysis of Zinedine Zidane’s often sub-par league displays for both Juventus and Real Madrid. Cox has always been able to spot patterns within games. Now his books are seeing them between leagues and eras. Revelatory stories, lucid tactics and wry anecdotes combine, without sacrificing the role of pure accident in determining any football result (something Cox well knows, as a Kingstonian fan). As Marcello Lippi says of the lessons learned at the Italian coaching school at Coverciano: “It does not give you truths, it gives you possibilities.”