This endearingly anachronistic range of player figurines may have lacked accuracy and interactivity, but they provided an early window into the world of football

27 February ~ It was in George’s discount shop in Crosby village that I first clapped eyes on a Kenner Sportstars figure. The very fact that these toys were available in the place known to all local residents as “the 50p shop” should have clued me in to the fact that they had probably been sitting in a box for a while – and the several-seasons-old kits they portrayed should have been an indicator, too. But as far as I was concerned, they were among the most exciting things I’d seen since recently discovering the game of football.

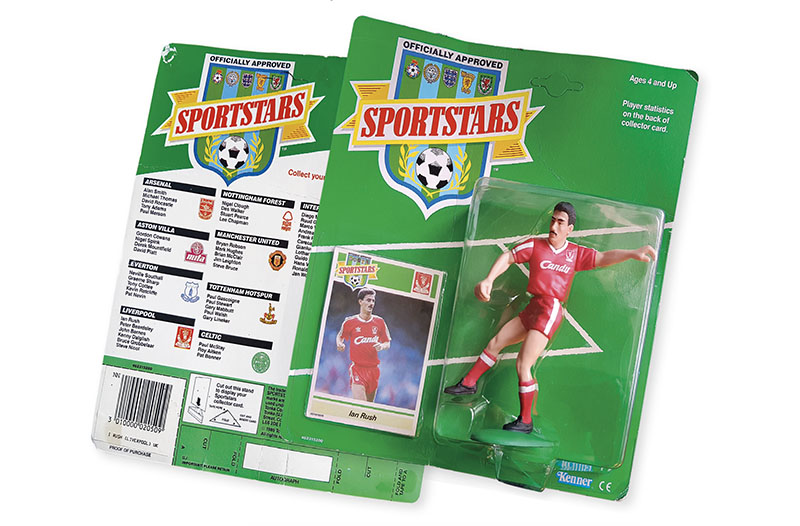

Encased in moulded plastic against a bright green card background – the football-pitch-styled packaging proving every bit as alluring to me as the boxes Subbuteo came in – these four-and-a-bit inch figures bore exotic names and team colours that up until this point I’d only read about in Roy of the Rovers and Shoot. Marco van Basten, Lothar Matthäus, Gary Lineker, Diego Maradona, Hans van Breukelen… even Nigel Spink.

The majority of toys relating to football are table-top games of some kind – which makes sense, given that to “play at” playing football, you’re going to want to be replicating a match. But the Kenner figures, a 1989 offshoot from an American line of sporting toys named Starting Lineup (and notably visible in the 1990 film Home Alone) aren’t for pretending to play matches with. There are no action features, no ball to propel, there aren’t even enough of them to put together a full team.

Instead, they capture a single moment in time: a slide tackle, a stretching save, a lashed volley. In fact, they ascribe the same single moments in time to several players at once – their mass-produced nature means that there are only around five or six pre-fabricated poses for the players’ bodies. They feature incredibly generic faces, too, with only a moustache here or longer hair there to tell you you’re meant to be looking at Derek Mountfield or Ruud Gullit.

Though if all else fails, they have the players’ surnames printed on their backs above the shirt numbers – a doubtless American-influenced innovation that predated European football’s use of the feature by several years. This anachronism isn’t the only inaccuracy on the kits, which also fail to feature manufacturers’ logos (or trademarked design elements such as the Adidas three stripes), although the machine-printed team badges and sponsor logos are faithfully reproduced.

So if they were out of date when I started to collect them, and they were never really that accurate in the first place, why does merely looking at them hold such an attraction to me? Why do I have a mint-on-card Ian Rush model, bought from Ebay when I was far too old to know better, affixed to my wall next to a similarly mounted Dapol figure of Sylvester McCoy’s Doctor Who?

It comes back, really, to that capturing of a moment in time. But now, if I look at the figures they don’t capture a moment in the players’ lives, but in mine. They capture a time when football was new and exciting to me – an entire world that I was discovering. It’s through excitedly swapping these figures with friends at school that I learned that Steve Nicol played for Liverpool and Scotland, that Everton’s goalkeeper was named Southall, that Bayern Munich were sponsored by Opel (even if I didn’t know then what Opel was).

Not to mention, of course, that they capture a time when football itself was simpler. The figures were simplistic because they came from an era when marketing didn’t have as big a hold on the game. They wouldn’t get away with those design inaccuracies now, nor would still selling figures in 1989-90 kits all the way into 1991 be acceptable.

And yet the mentality that these figures drove in me can still be seen in kids today. Learning about the world’s players and collecting iconic representations of them still happens – it’s just that it’s now as digital sticker packs bought for in-game currency in FIFA. No doubt, in 30 years’ time the kids of today will be just as nostalgic for that fictional world – and although they won’t be able to get them from Ebay and stick them on their office walls, that’s probably healthier. Seb Patrick

This article first appeared in WSC 384, March 2019. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here