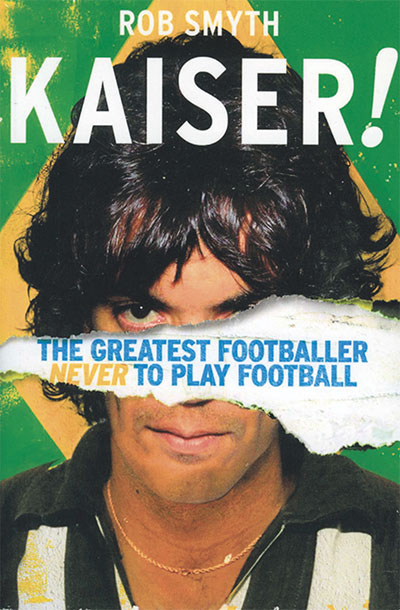

by Rob Smyth

Yellow Jersey Press, £9.99

Reviewed by Paul Rees

From WSC 379, September 2018

Buy the book

On several occasions in this racy book, Guardian writer Rob Smyth references Catch Me If You Can, Steven Spielberg’s 2002 biopic of an engaging conman. Spielberg’s slick movie is a favourite of Smyth’s central character, Carlos Henrique Raposo. Fittingly, since the so-called Kaiser also has a questionable moral compass and distant relationship with the truth.

On the surface, Raposo’s extraordinary story is likewise one of dash and daring. Born in Porto Alegre in southern Brazil in 1963, by Raposo’s own account he was abandoned by his single mother and raised in poverty by adoptive parents in Rio de Janeiro. Like generations of Rio street kids, Raposo grew up playing football barefoot on the local dirt-tracks and as a youth was picked up by scouts from Botafogo, one of the city’s four top-flight teams. At Botafogo, Raposo claims his imperiousness on the pitch reminded his fellow hopefuls of the legendary German captain Franz Beckenbauer and that this earned him his nickname.

At all events, this positive impression of Raposo’s footballing gifts was fleeting. One contemporary records how Raposo could barely control a ball and he was soon let go by Botafogo, although not so that this deterred him. In Smyth’s breathless telling, Raposo nevertheless managed to spend the next 26 years thriving as a professional footballer, flitting from one club to another in Brazil and as well in the leagues of Argentina, North America and France, but without ever once playing in an actual first-class game.

Smyth attempts to portray Raposo as a shameless, though endearing, schmoozer, able to talk his way into securing multiple contracts and then through the simple means of feigning injury in training, avoid being found out as a charlatan. He is seen to have passed through the ranks of each of Rio’s major sides and that of the then-World Club champions Independiente of Argentina, rubbing shoulders with such greats as Bebeto, Romário and Zico. Smyth does a solid job of showing how Raposo’s unlikely path might have been smoothed by the chaotic nature of Brazilian football at the time, with the clubs habitually run by Mafioso-style bosses and riven with corruption, a more widespread lack of medical expertise in the game, and the vagaries of the pre-social media world.

However, the book stumbles on two significant obstacles. Despite Smyth’s best efforts at burnishing, the grubbier aspects of Raposo’s character make him tough to like, much less admire. He is shown to be a freeloader, blackmailer, glorified pimp and as being unreliable. Inevitably, this last trait makes his more outlandish assertions suspect at best, and so that the reader is left with nothing of substance to hold onto and the sense of being taken for a ride. In the end, even Smyth admits to having his doubts, though perhaps the defining view on Raposo is attributed to Zico. “He’s an affront to professional football,” Smyth quotes the former Brazilian striker, “and a complete liar.”