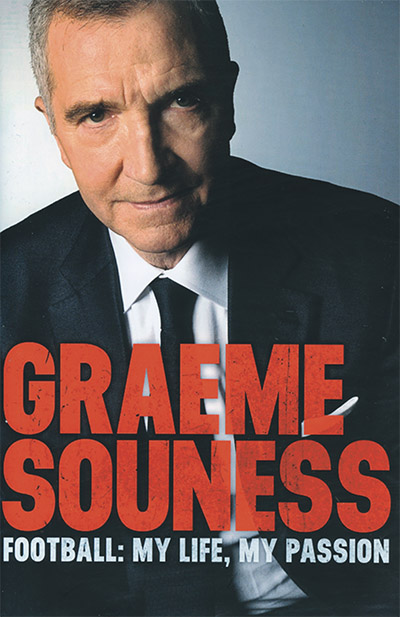

by Graeme Souness

Headline, £9.99

Reviewed by Peter Brooksbank

From WSC 378, September 2018

Buy the book

To football supporters of a certain age, Graeme Souness was a snarling presence at the heart of the great Liverpool sides of the late 1970s and 1980s; a midfielder who, like his team, could effortlessly switch between the ferocious physicality of the British game and the more artful flourishes of continental football.

For younger fans, Souness is Sky’s irascible counterpoint to the cheery Thierry Henry; the perpetually unimpressed ambassador of an obsolete brand of football, doling out forthright punditry with the indignant demeanour of a man who’s just had his tea interrupted by a cold call about PPI.

In truth, there’s not much in this autobiography – co-written with Douglas Alexander – that will seriously challenge either of these perceptions. It begins with “Lucky Man”, a rambling, pinballing introduction in which Souness is very keen for you to understand how “blessed” he feels to still be earning a living from football, albeit a feeling he still contrives to convey in a tone of thinly disguised menace. Souness manages to last five pages before launching the inevitable first assault on contemporary football. By page seven he’s jabbing a finger into its ribs. “My request to the players is: just put a bit more back in,” he lectures. There are still 261 pages to go.

But there’s actually something quite comforting about the tetchy rants which spring unexpectedly from benign anecdotes about things like hotels – a familiarity which borders on the familial. You can sense those narrowed, threatening eyes glowering back at you from the page, daring you to justify Mesut Özil’s wages.

Many of the stories – Liverpool’s dominance, Rangers, Ali Dia – we know already. It’s the flippant asides that provide the colour, such as Souness concluding a story about Scotland’s 1978 World Cup campaign by boasting about his hair. “I should also point out that in a squad infamous for its perms, mine was natural,” he declares, a sentence you imagine was originally sent to his editor in 24-point ultra-bold font, underlined in red ink. Twice.

Other disclosures are just a bit odd, such as when Souness reflects on a trial spell for West Brom in a chilly Whitley Bay. “It was blowing a gale,” he recalls. “My short-sleeved shirt didn’t provide much protection, although I greatly enjoyed my first prawn cocktail during that trip.” Later, he talks of the “debauchery” of a trip to Canada, one which presumably involved a lot more prawn cocktails.

There are flashes of deeper stuff: the flaws, doubts, traumas and regrets carried by many ex-pros and from which even Souness is not immune. There’s sadness at leaving Blackburn too soon. A sudden feeling of vulnerability after heart surgery. The public death of Jock Stein. But these moments are fleeting and underdeveloped, not given further scrutiny, and before long we’re back where we started, a disdainful Souness poking at the state of modern British football as though it were a crap dinner in a rubbish restaurant. Or a bad prawn cocktail. Some of us wouldn’t want him any other way.