The age at which children are signed by professional clubs is getting younger, but the consequences for those stuck in the world go far beyond disappointment at not making the first team

31 May ~ Last year, it was reported that ten-year-old Alessandro Cupini had been signed up by Roma’s coaching academy. From his name, this possibly doesn’t look surprising until the detail is added that he is moving – along with his grandparents, parents and three‑year‑old sister – from Kansas City. Cupini’s story is not rare and Roma are not the first club to entice child players from abroad – Barcelona “signed” seven-year-old Enzo Romano from Cardiff, 11-year-old Manu from Brazil and, of course, a 13-year-old Lionel Messi from Argentina. Real Madrid are no slouches in attracting pre-teen talents either. Like Barcelona, Real hold trials all over the world from Europe to Japan and Australia with a select few children flying to the club’s La Fábrica Youth Academy. These trials resulted in the club signing 11-year-old Joshua Pynadath from California; now, at 16 years old, an Ajax player. Fourteen-year-old Lateef Omidiji also made the transatlantic move from the US to the Netherlands and is now playing at Feyenoord. It hasn’t been just mainland European clubs that sign young foreign schoolboys either; Manchester United brought a nine-year-old Rhain Davis and his family from Brisbane in 2007. Arsenal brought Anthony Stokes and his family over to London from Ireland at 15.

What is, perhaps, surprising is the mainly positive reports of such signings with no issue being taken with multi-million pound companies moving children – albeit with parental approval and complicity – from their home countries. Not only this but there are many more instances of very young British boys travelling long, if not as vast, distances regularly at the behest of professional clubs. English academies take interest in pre-teens often and players can sign up with professional academies from nine years old. Previous to this age, however, players can sign on for clubs’ development programmes and train with them.

There have been strict regulations whereby under-12s can only travel a maximum of 60 minutes from their home (90 minutes for 13-16-year-olds). However, since the Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP) was introduced, academies designated Category One are not limited to such catchment areas and can recruit nationally. Even before the EPPP, clubs were able to play the system – establishing a satellite academy at the edge of their catchment area attracting boys who were a further 60 or 90 minutes away. The academy of a current Premier League club – renowned for bringing young “local” boys through their system – used this to bring in players from distances of 120 miles away. This meant two-hour round trips just for training on school nights, four-hour round journeys for children for “home” matches and longer for away games.

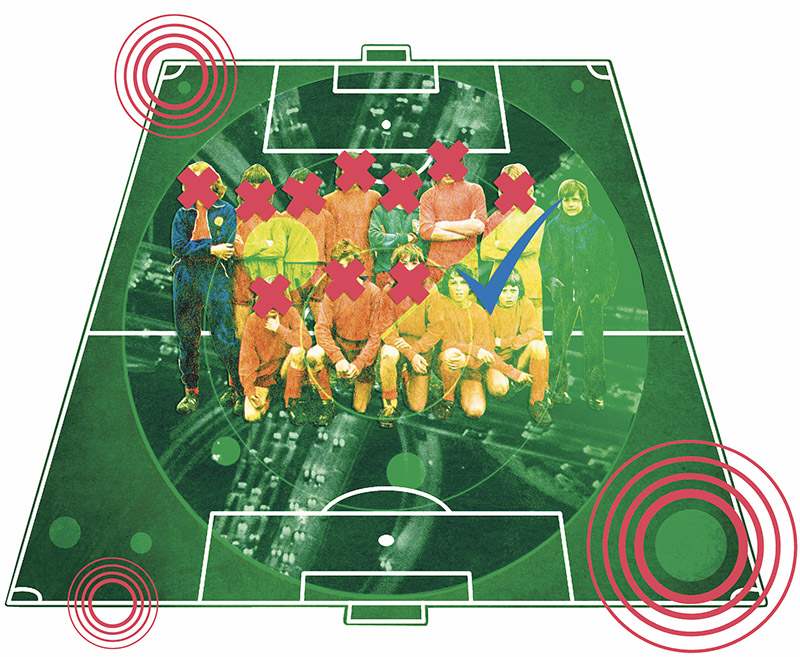

Aside from the travelling involved, many young hopefuls don’t realise that academies only really pinpoint one or two players from each cohort that are likely to make the grade but they need a team of other players around them. As such, the attrition rate for academy players is eye-watering, with less than one per cent becoming professional players. Obviously, the rejected players could end up at non-League clubs or even come back into the professional game. However, many have to go back to grassroots clubs to try to reboot their careers, with many giving up the game altogether.

Falling out of love with football is a sad enough outcome for children who are often released at age 16 – while they are studying for their GCSEs – with no follow-up support. However, there are more serious consequences – a research study carried out by Teesside University in 2015 found that over half of the players released were suffering “psychological distress”. There have been stories of players committing suicide and others turning to drug dealing after being dropped from academies. Even for those who remain involved, being in the system can have a negative impact on their future. A secondary or even primary school age boy signed to a Premier League club is in danger of seeing education as unnecessary with a tangible alternative of being paid thousands a week playing full-time football. It would be a hard job for any teacher or parent to keep that child’s feet on the ground and eye on school work if they aren’t interested academically.

There does appear to be tacit acceptance in football, in the media, among parents and in wider society that football clubs can court players from their earliest years, persuade them to travel for hours only to reject them at their most vulnerable age. No other professions (apart from, perhaps, the performing arts) would be allowed to effectively have children carrying out near-adult roles while they are still in full-time education.

Children should be shielded from any rapacious multi-million-pound industry. A strategy for this is restricting professional clubs from approaching a child until they are 16. Up until then, they should only be allowed to play for their local grass-roots club: keeping the enjoyment in football for the children; cutting down drastically on travelling time; maintaining focus on education. Clubs will find ways to circumvent this – perhaps buying a child’s family a house so that they are “local” to a compliant feeder club. However, the lack of guarantee of signing them until they are out of full-time education should make it less worthwhile to do this.

The academy system is so entrenched in our culture, however, that no one would think of dismantling it. There are too many vested interests: clubs, parents and children. Of course, the government and football authorities should protect the latter two, who may not know better, but it is doubtful they are bold enough. With Barry Bennell’s crimes while working with children at professional clubs dominating the media recently and sexual abuse at clubs rightly being investigated further by Clive Sheldon QC, perhaps there are more widespread welfare issues occurring at academies that should be scrutinised and acted upon. Marc Thomas

Illustration by Matt Littler

This article first appeared in WSC 375, May 2018. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more details here