Bloomsbury, £20

Reviewed by Seb Patrick

From WSC 364, June 2017

Buy the book

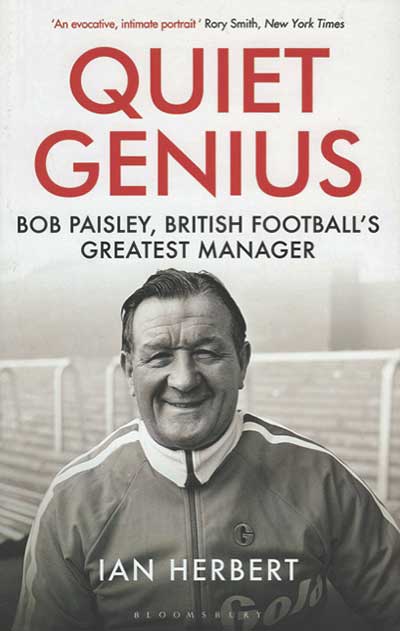

Look in any sports books section and you’ll find several biographies of Alex Ferguson, Brian Clough and José Mourinho – but next to nothing about Bob Paisley, despite him being the only British manager ever to win three European Cups. As such, Ian Herbert’s new biography can lay reasonable claim to being definitive simply by existing.

Herbert has a somewhat thankless task in trying to wring drama out of Paisley’s story – for a man who spent 50 years at Liverpool as a player and manager, overseeing the club’s most successful period in the process, there’s precious little room for sensationalism. Paisley makes smart and insightful decisions while often struggling to explain them.

While his more storied predecessor Bill Shankly was the one who loudly proclaimed a devotion to socialism, what comes across from Quiet Genius is that it was Paisley who truly embraced a spirit of collectivism. At every turn, his actions are rooted in the idea of Liverpool as an organisation being more important than any one individual – with little regard shown for whether he himself would be liked or revered personally.

This desire to boost Liverpool and their spending power at all costs results in the apparently old-fashioned soul becoming a man who would embrace sponsorship opportunities, and also signings that were designed solely as corporation tax write-offs (including a trio of young Irish players who never got into the first team). There’s a similar dichotomy in his apparent mistrust of continental clubs, while at the same time developing tactical innovations inspired by them.

Though clearly never an inspirational figure like Shankly or Clough – his interactions with players frequently found him on the back foot, and he had a particular issue in dealing with those not in his first XI – Paisley comes across as a decent if hard-nosed man, who made the most of the attributes he did have (namely, an innate ability to read football matches) to overcome his social limitations.

It’s also interesting to note which are the select few players that Paisley actually bonded with personally, the most prominent – and surprising – being Graeme Souness, the “Champagne Charlie” who nevertheless embodied the do-or-die spirit Paisley sought to foster, and whose affection for the manager who made him captain is clear and sincere.

With so little of Paisley’s own voice existing in the world, Herbert instead relies on an extensive set of interviews to tell the story. While the words and opinions of players and fellow staff from that era are largely familiar, though, it’s the contributions from family members that help to flesh out Paisley’s character. In particular, learning more about his largely under-documented playing career helps to offer insight into his demeanour as manager, while the story of his life afterwards – gradually slipping away from the club, never managing again, and succumbing to Alzheimer’s – is briefly painted in moving and regretful tones.