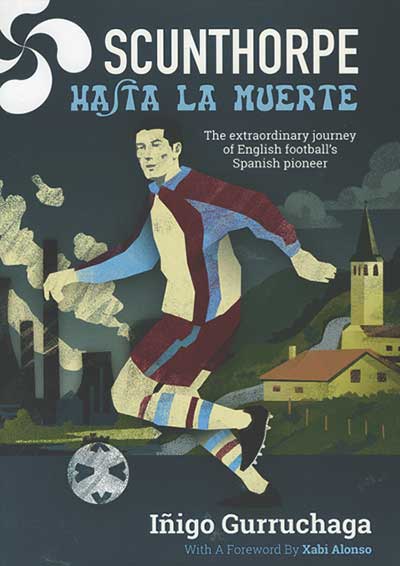

The extraordinary journey of English football’s Spanish pioneer

De Coubertin Books, £14.99

Reviewed by William Abbs

From WSC 361, March 2017

Buy this book

Those who follow Scunthorpe United will remember Alex Calvo García forever for his goal in the 1999 Division Three play-off final. But anybody who was consuming their lower-league football through Ceefax around the turn of the millennium will be pleased to be reminded of the Spanish midfielder’s time in England too, when an exotic-sounding name among the scorers on page 316 was still a rarity.

While García’s billing as “English football’s Spanish pioneer” is a little over the top – fellow Basque Emilio Aldecoa played for Wolves and Coventry in the late 1940s – the circumstances behind the arrival of the former Real Sociedad trainee in Division Three were still relatively unfamiliar and a sign of how the Bosman ruling was changing the game, even far below the Premier League. Like Aldecoa, who came to England as a refugee, García’s family felt the force of Francisco Franco’s regime when his father was beaten and imprisoned for carrying left-wing literature.

With García out of contract in 1996 after leaving Eibar, he consults his girlfriend about a move abroad and his agent secures a trial at Glanford Park. Scunthorpe’s manager at the time, Mick Buxton, is impressed enough to offer a deal worth £525 per week – double what the 24-year-old had been on in Spain. After a difficult first few months, played out of position and an outsider in the dressing room (“the lower divisions are the last refuge for British players”), a turning point comes through a heart to heart with new boss Brian Laws, the chairman’s daughter translating.

By the time of the game at Wembley against Leyton Orient three years later, García is one of the most popular team members. His header to win promotion makes him a hero. Scunthorpe return to Division Three the following season but García, now settled in the area and writing a column for the local paper, remains loyal. He stays with the club until 2004, helping them to avoid relegation from the Football League.

Though ostensibly a work of biography, the player himself is oddly absent from large parts of the text. Inigo Gurruchaga devotes significant passages to essays on football culture, local history, films and novels. Some of the topics are pertinent to García’s story: five pages are given over to the career of one of his boyhood idols, Kevin Keegan, beginning as it did with Scunthorpe. However, while a lengthy section about the role of the church in encouraging good citizenship through sport is interesting, particularly given Methodism’s ties to Lincolnshire, it’s perhaps a subject to save for a different book.

Some sections feel a little stilted and the repetition of the mantra “Football is a game which commences at three o’clock in the afternoon on an English Saturday” is grating, but this is a translated work and it does not spoil Scunthorpe Hasta La Muerte’s charm. Although it was written first for a Spanish audience likely to be as unfamiliar with Scunthorpe – the town and the team – as García was before his move, fans of the Iron will find plenty to enjoy, as will those open to their football reading being sprinkled with references to Get Carter, Joan Plowright and Norse etymology.