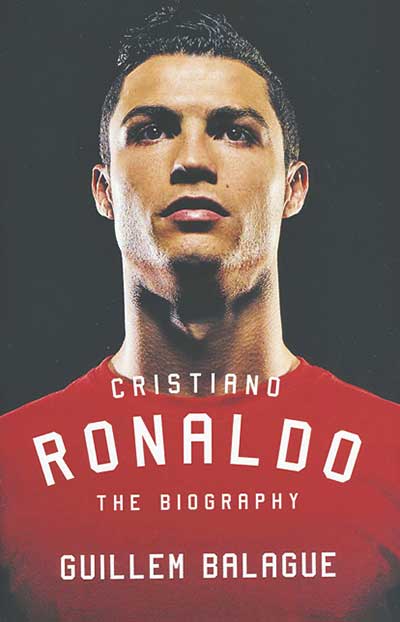

by Guillem Balague

by Guillem Balague

Orion, £20

Reviewed by Joyce Woolridge

From WSC 349 March 2016

Throughout the 350 and more pages of his “definitive” biography of Madeira’s finest player, Guillem Balague never runs out of steam or ways in which to point out that his subject is insecure, selfish, self-obsessed and immature. You don’t need to call in Freud to understand Balague’s negativity, just the 18-page prologue which demonstrates how miffed the author is not to have the sort of co-operation given by Lionel Messi in a previous biographical outing.

The opening chapter involves trips to Funchal to research Ronaldo’s parenting, from an alcoholic, frequently absent father and hard-working, doting mother who held the family together. This allows him, according to Balague and one of his several experts, “the freedom necessary to become the player that he is”, while “at the same time creating the space for the development of his selfishness, intolerance and arrogance”.

There is then an excellent, bordering on sympathetic, account of the 12-year-old Ronaldo’s talents when he arrived alone in Portugal. Indeed, the subsequent chapters about his early years and development as a footballer are among the strongest in the book, though even what seems like the most innocent of statements from Ronaldo, such as that he wanted a son who played football and that he would be happy if his son resembled him, are given an insinuating, psychological twist by the author: “Shall we just say that many fathers have fantasies like this? Or maybe it reflects something deeper.”

The sections which deal with Ronaldo’s time both at Manchester United and Real Madrid show Balague at his best, uncovering the complexities of the business dealings and club politics and discussing how Ronaldo was received by and operated in both, very different, dressing rooms. At United, he transforms himself physically, while being kicked and shouted at by the Nevilles and being made fun of constantly by everyone else. At Madrid, Ronaldo works to subjugate the play to serve his own ends while his agent Jorge Mendes strives to make him appear a better person so that someone else other than Messi can win the Ballon d’Or from time to time.

Although there is appreciation of his sublime skills and the hard work which developed them further, there is not enough football here. There are 11 pages dealing with Florentino Pérez’s re-election as Madrid’s president, whereas the 50-goal seasons rate a few paragraphs. And even when Balague is assessing what he considers one of Ronaldo’ finest performances, the second leg of Portugal’s qualification play-off with Sweden for Brazil 2014, he spends as long describing how he watched it in a bar in Morocco where Ronaldo was booed throughout.

As for his time at Madrid, Balague’s conclusions are that Madrid fans would be happy to see him leave and that, yes, he may have scored over 50 goals in five consecutive seasons, but he has always played for himself and “might Cristiano’s obsession with scoring goals have affected the team’s performances in such a way… as to hinder their chances in long competitions?”.

Balague is prone to ramble: there is a lengthy extract from William Dalrymple’s Nine Lives which is supposed to illuminate the footballer’s immersion and ecstasy in big games and some rather more entertaining diversions into Portuguese history and why Catholicism leads to diving. And it is undoubtedly a strength that he is never reverential in the slightest towards his subject. However, by the end the interminable detailing of examples of what the author sees as Ronaldo’s legion of failings becomes boring and vaguely unpleasant.