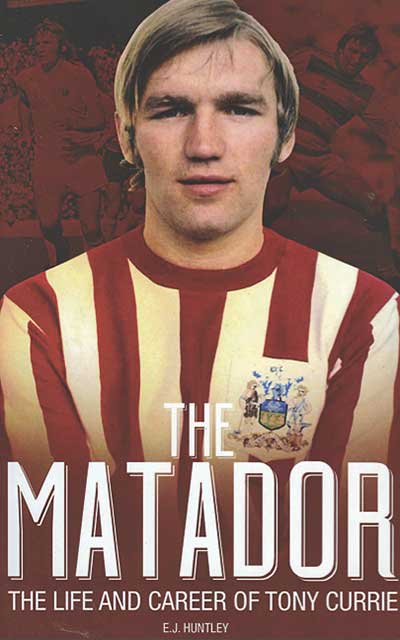

The life and career

of Tony Currie

The life and career

of Tony Currie

by EJ Huntley

Pitch Publishing, £12.99

Reviewed by David Stubbs

From WSC 349 March 2016

There’s a strange fascination about Tony Currie that runs in parallel with the late David Bowie, or even the school of provocatively effeminate wrestlers of the early 1970s such as Adrian Street – glam Englishmen whose apparent purpose was to raise the hackles of a more stolid, crewcut older generation with their flamboyant, long-haired antics.

In 1975, Currie’s Sheffield United were thrashing Leicester City 4-0 when he and Leicester’s Alan Birchenall collided in the penalty area. “Give us a kiss, TC,” Birchenall said, and Currie, who was fond of winding up crowds by blowing kisses at them, duly obliged. The furore this caused exceeded, if anything, that provoked by Bowie putting his arm around the shoulder of guitarist Mick Ronson during his Top of the Pops performance of Starman. The incident was raised in the House of Commons, while Birchenall and Currie were besieged with letters from right-wing groups stating that should they come to power, “perverts” like them would be shot.

Currie is generally grouped with footballers such as George Best and Stan Bowles; flamboyant 1970s specimens whose antics enraged their elders but have become too soon extinct in the over-moneyed, pragmatic modern game. EJ Huntley’s account of Currie’s life does not itself sparkle, or particularly celebrate the parallels between Currie and the wider 1970s pop culture. His prose is stolid, in which stonewall penalties, pastures new, majestic form, winning ways and releases down the right flank greyly abound. It’s strictly football.

But then, while Currie enjoyed touches of showmanship, off the field, he was a blameless introvert and family man. If you were looking for eccentric flamboyance, then Sheffield United midfield enforcer Trevor Hockey, of all people, was your man; driving around in a velvet-covered Triumph Vitesse and the owner of a pink piano and studying archeology books as a hobby. None of that for steady Tony, who resented that his languor on the ball was mistaken for laziness, or the assumption that he went out on Best-style drinking rampages when he was most likely at home with a cup of tea.

Huntley provides a highly serviceable account of Currie’s football career, not least his days at Sheffield United, culminating in the “quality goal by a quality player” eulogised by John Motson on a relatively rare Match of the Day appearance in 1975. But a relative lack of such exposure meant Currie was constantly overlooked. His heart, he admits, was always at Bramall Lane but he moved on to Leeds, then QPR (captaining them in the 1982 FA Cup final), before ending up at Torquay and then a failed stint playing in Canada.

A naivety regarding contracts saw him at 33 divorced and living at his mother’s council house drinking a bottle of whiskey every other day before finding employment in the Football in the Community project. Would he fare better today? I suspect so. Ironically, as he protests throughout this book, he was a deceptively hard worker whose lack of career opportunism, rather than supposed gadabout ways, was his undoing.