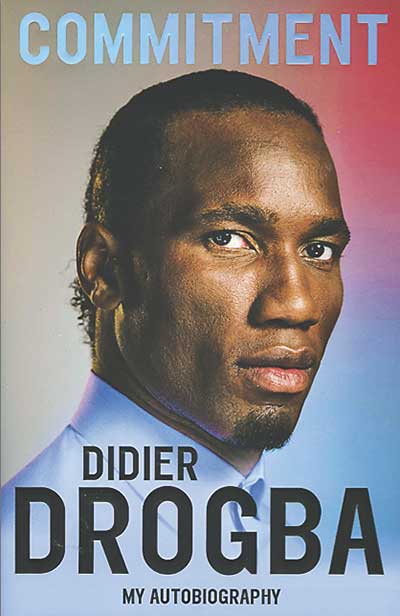

My autobiography

My autobiography

by Didier Drogba

Hodder & Stoughton, £20

Reviewed by Si Hawkins

From WSC 348 February 2016

A couple of lines late in Didier Drogba’s autobiography really drive home that this isn’t your average burly striker life story. “On November 2009 I teamed up with Bono to help launch an initiative with Nike on the eve of World Aids Day,” Drogba recalls, before rattling through his UN work, including “mobilising people to eradicate the use of cluster bombs/munitions”. Clearly we’re in a different ballpark to, say, Micky Quinn’s Who Ate All The Pies.

Drogba, now of Montreal Impact but possibly back at Chelsea by the time you read this, is something of a global statesman these days, so his book is as scant on lurid tales as you might expect. Still, the conservative tone can’t entirely dull a remarkable career. It’s barely fathomable now that a player regarded as a legend at Stamford Bridge was repeatedly booed by his own fans in 2005-06, for unsporting behaviour. Nine years on, the returning hero helped new boy Diego Costa “adjust to English football”, although it’s hard to imagine Costa ever commanding similar esteem.

One early difference here from most player autobiographies: the childhood chapters are interesting. Young Didier was sent from the Ivory Coast to stay with his footballer uncle in various French locations, although the book’s greatest admission occurs before that. His mother “nicknamed me ‘Tito’ after the Yugoslav leader whom she much admired”. Sadly that’s all Didier – or rather his ghostwriter, the journalist Debbie Beckerman – wrote about the Drogbas’ political leanings, so we’re left to ponder how that familial fondness for benevolent dictators extends to José Mourinho and Roman Abramovich, both of whom he lauds regularly here, like a loyal subject. Or a kindred spirit.

“Tito” insists that he’s naturally shy, but Chelsea fans will recall a propensity for furious outbursts, particularly in vital Champions League games. He can’t help chastising old colleagues here too, and the Chelsea chapters are revealing in light of recent events. Of Mourinho’s first sacking, Drogba suggests that certain players “hadn’t done all they could on the pitch to help his cause”, which sounds familiar. But then the pattern repeats with Chelsea’s subsequent bosses, and Drogba is a major antagonist. André Villas-Boas had scouted him for Chelsea, but when the beleaguered manager tried to build bridges with the team, his centre-forward was the one player to openly criticise his tactics: “As ever, I spoke up.” Villas-Boas never recovered.

He and Bono clearly have much in common too. Drogba openly admits to domineering lead-singer syndrome with the national team, which “affected team spirit and had a knock-on effect on some of our games”. But then Drogba had begun to transcend football, while also using it to help heal a nation hurt by civil war. One impassioned post-match plea for peace was aired regularly on TV, and he even dragged the team to play in a no-go rebel zone. His commercial earnings now fund the clinic-building Didier Drogba Foundation, including those from this autobiography. Like its star, Commitment is ego-fuelled and prone to occasional diatribes. But it means well.